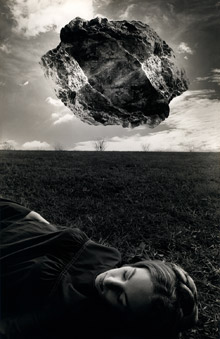

MAGRITTE'S TOUCHSTONE (FIRST VERSION) Uelsmann's pictures hark back to the surrealism of Dalí, Magritte, and Buñuel as well as anticipating the look of Photoshop and Gregory Crewdson. |

Jerry Uelsmann's photos are like hallucinations. A glowing woman keeps reappearing among trees and in reflections in still water below. A flaming desk appears in the woods of Yosemite. A sleeping nude woman's body morphs into a river raging through a canyon. In a wood paneled room, a tiny man walks across a book on a desk toward a map, and the room's ceiling above is missing, revealing clouds and a blast of sunlight.

>> SLIDESHOW: Jerry Uelsmann at the PEM <<

"The Mind's Eye: 50 Years of Photography by Jerry Uelsmann" at the Peabody Essex Museum (161 Essex St, Salem, through June 30) is a ravishing retrospective of a Florida photographer whose pioneering darkroom sleight of hand earned him the nickname "the father of Photoshop."

The 77-year-old Detroit native found his signature style around the time he moved to Gainesville to teach photography at the University of Florida in 1960. "I went from [grad school] to being the only photographer in an art department," Uelsmann recalled at the PEM press preview. "So when I got together with my friends, we talked images and feelings and ideas. That was a 10-year period when I wasn't really talking to other photographers."

By the 1970s, Uelsmann was embraced by the Museum of Modern Art and, says Peabody Essex curator Phillip Prodger, was "the most widely collected photographer." His medium-format, black-and-white photos had the crisp, tonal richness of Ansel Adams-style high-Modernist photography, but with experimental darkroom technique. It didn't hurt that his dreamscapes resonated with the ominous atomic age (in 1967's Apocalypse II, the mirrored negative of a tree becomes a mushroom cloud) as well as the trippy, mind-expanding Age of Aquarius.

In Magritte's Touchstone (first version) (1965), a boulder hovers in the air over a woman asleep in a wide, empty lawn. The woman is pushed into the foreground of the deep space for a sort of intimate voyeurism. Uelsmann's sharp focus pronounces the textures of the rock and the braids of the woman's hair. The effect is a sensual, dreamlike hyper-reality in which the boulder looms as a threat. In other photos, a mirrored birch tree suggests a Rorschach-test totem pole, a block of air seems to be pulled out of a sky, a rowboat hovers over a waterfall.

As fine-art photography turned more toward deadpan documentary, Uelsmann's work came to seem hokey. And feminism made his sexy naked ladies feel passé. He was sidelined, only fitfully receiving major attention. In retrospect, his pictures remain (mostly) fresh, harkening back to the surrealism of Dalí, Magritte, and Buñuel as well as anticipating the look of Photoshop and Gregory Crewdson.

Comparisons to Photoshop — with its endless possibilities and endless ability to reverse your mistakes — are misleading, though. Digital editing makes easy Uelsmann's complicated process, which requires setting up several enlargers with separate negatives to develop each print. Uelsmann is about virtuoso photographic printing, demonstrations of handcraft that push the process to its limits like a daredevil jumping his motorcycle over a canyon. When Uelsmann pulls off the incredible landing, it looks both easy and like magic.