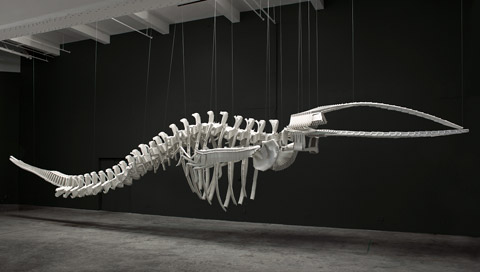

CETOLOGY Brian Jungen's sculpture assembles plastic lawn furniture into a monumental whale skeleton. |

The "chief" in Kent Monkman's Théâtre de Cristal (2007) looks like one of the Village People, in a feathered headdress, jockstrap, and platform heels. Shown in a film that's projected onto a faux buffalo-hide rug inside a teepee of glittering beads, the character captures a pair of primitive "European males" in loincloths. "It has become my life's work to make a record of them before they're obliterated completely," an intertitle says. The "chief" paints the white guys' portraits in between getting them drunk and feeling them up.

>> SLIDESHOW: "Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art" <<

The Cree artist plays his drag show for laughs, but underlying it are serious questions about white genocide of Native American societies, about the stereotyping of Natives, and about gays in America, as well as Native American society.

It's an audacious opening to "Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art" at the Peabody Essex Museum (East India Square, Salem, through April 29), proclaiming that Native Americans are still kicking (which shouldn't be news to anybody), they're critical, they're funny, and some are even gay. But immediately, curator Karen Kramer Russell backpedals. The words "gay," "queer," or "two-spirits" are apparently not part of the Peabody Essex's vocabulary. The closest the wall text gets is "Monkman examines sexuality and power dynamics between the colonized and colonizers. . . ."

This combination of audacity and reticence runs throughout the Peabody Essex's blockbuster survey of 73 works that sample all Native American art ever, making it simultaneously one of the most intriguing exhibits of the year and tear-your-hair-out frustrating. The research is comprehensive, the art frequently amazing, but the packaging is square, retrograde, timid.

The works speak of nature, decoration, dance, tradition, and how Native American peoples have been stereotyped by the dominant white culture. Dazzling examples of traditional crafts include century-old Dakota and Kiowa cradleboards, bears glowering down from a 19th-century Tsimshian totem pole, a translucent 1820s cape stitched together from sea lion intestines, and a Tlingit Chilkat blanket woven with diving whale motifs that is believed to the oldest (180 years) surviving example of its type.

Contemporary works include a photo of Puyoukitchum artist James Luna's landmark 1987 performance in which he dressed in a loin cloth and laid like a specimen in a case at the San Diego Museum of Man; Cherokee photographer Thomas Joshua Cooper's paired 1998 to 2001 photos of the sea seen from Plymouth in England and Massachusetts, the origins of the Pilgrims and Indians legend; and Dunne-Za sculptor Brian Jungen's 2002 Cetology, plastic lawn furniture transformed into a monumental, funny whale skeleton that prompts gloomy meditations on the environmental threat of plastics, pollution, and global warming.

The exhibit is impressive in its scope, but Kramer Russell basically includes only traditional crafts by dead artists and "fine" art by Native Americans of the past few generations, stuff that too often reeks of standard-issue Euro-American art training in North American graduate schools. This erases the many Native Americans doing excellent work in traditional crafts today, emphasizes change and progress over continuity, and implies that the old traditions have been supplanted by modern-art Manifest Destiny.

>> SLIDESHOW: "Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art" <<

What's more, it's easy to walk through the show without noticing any angry Indians. Imagine an exhibit of the whole history of African-American art that flashed little anger and muffled Black Power. As the Peabody Essex's fundraising now exceeds that of the Museum of Fine Arts and its exhibits have become world-class, does the museum also have the moxie to substantially address the big issues?

Read Greg Cook's blog at gregcookland.com/journal.