Photography is always seducing us with its whispered promise that what you see is what you get. No matter how many times Trotsky gets airbrushed out of Soviet photographic history or model Filippa Hamilton's waist magically sheds pounds via Photoshop, we still want to believe that the camera doesn't lie.

Since the 1970s, artists operating in this gap between truth and fantasy have become one of the primary branches of art photography — including Gregory Crewdson's eerie twilight dreams that he has staged in the Berkshires as well as the images of Duane Michals, Jeff Wall, Annie Leibovitz, William Wegman, Pierre et Gilles, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Ruud van Empel, Carrie Mae Weems, Nicholas Kahn and Richard Selesnick, David LaChapelle, and Justine Kurland.

After photographers in much of the 20th century had strived for ever-more-truthful realism, their next move was to explore the possibilities of unreality, of fictional constructs. They range from what Wall calls "near documentary," to personal ritual, to fashion fantasias, to Crewdson's Hollywood spectacles. It was a post-modern echo of late-19th-century photos that aimed to demonstrate that photography was as legitimate an art as painting by staging religious and mythical tableaus like F. Holland Day's self-portraits as a crucified Jesus (part of the Day survey "Making a Presence" at Phillips Academy's Addison Gallery of American Art, 180 Main St, Andover, through July 31).

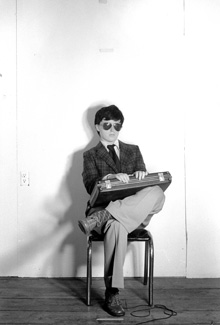

The founding mother of this Hollywood-esqe revival is Cindy Sherman, who circa 1976 began staging photos that imitated the look of movie stills. These images are at the heart of "In Character: Artists' Role Play in Photography and Video," also at the Addison through July 31. The seven artists here not only direct, but star in these self-portrait performances.

Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York | Cindy Sherman, Untitled, 1976/2000 |

Sherman dresses up as stock characters of a murder mystery (blonde starlet, maid, mobster, bathing beauty, guy in ascot) or bus passengers (tired woman clutching shopping bag, pimply guy in sports shirt, blonde girl in short skirt). Her later work uses her transformations into B-movie women in danger, Madonnas from old master paintings, and aging society ladies to speak about sex, vulnerability, womanhood, misogyny, beauty, aging, and American mores. The two 1976 series represented here are less developed, more just a game of dress-up that relies too much on stereotypes.Sherman's tactic is most striking— at least at this stage of her career — when she gets her characterization wrong by putting on blackface to portray an old black lady in a scarf and heavy coat or a smiling woman with wavy hair in a mini-skirt and platform heels. Sherman's makeup skills were then rudimentary yet still naturalistic; her blackface, though, reads not as an exploration of racial stereotypes but an ugly cartoon. She probably realized her error, because she seems to have avoided blackface since then.

A number of the photographers falter as they portray types instead of people. But Gillian Wearing's posing as her parents, siblings, and 17-year-old self in disconcerting waxy masks feels haunted by the legacies of family relations, genetic inheritances, and aging.