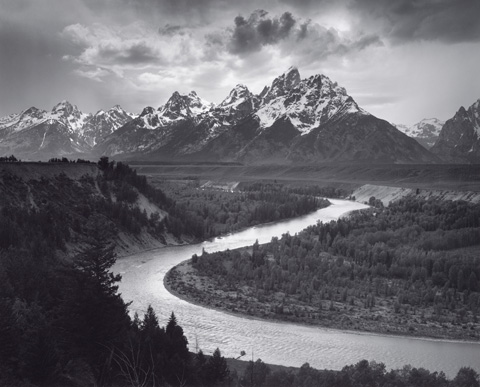

THE TETONS AND SNAKE RIVER, GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK, WYOMING Adams achieved

the same dazzling abstract detail as his modernist peers by stepping way, way back. |

In the last gallery of "Ansel Adams: At the Water's Edge" (at the Peabody Essex Museum, East India Square, Salem, through October 8 on their site) hang three impressively giant photographs. In the center is Gravel Bars, American River, a nine-foot-tall print from about 1950, looking along a wooded river canyon. The photo is so big that you feel like you're there, gazing down over the treetops in the foreground, and gliding above the shallow, rocky water.

>> SLIDESHOW: "Ansel Adams: At the Water's Edge" <<

The show aims to reframe our view of the famed landscape photographer. "Water was his siren song," curator Phillip Prodger writes. "Water, for Adams, was an insistent and abiding passion." Adams (1902-1984) certainly photographed water, but the more than 100 photos in the museum's summer blockbuster — of Yosemite lakes and waterfalls, Pacific shores, Yellowstone geysers, Alaskan rivers — don't convince that it was among his central themes. Gravel Bars, a bland composition made breathtaking because it was printed so big, is more about the canyon than simply water. Heck, only one of the four signs introducing each of the exhibit's galleries substantially addresses water. The theme doesn't seem to emerge from or illuminate the photos. By missing what Adams is really about, Prodger assembles a disappointing selection of outtakes from the work of one of the greatest artists of the past century.

What makes Adams great are his images of American wildernesses — rock and trees and occasionally water running through them — so majestic that you practically hear angels singing from the billowing clouds. Whereas his modernist peers tended to photograph close up, favoring sensual surface detail and abstract pattern, Adams achieved that same dazzling detail but stepped way, way back. His crashing waterfalls and rivers become vague. The open, repeating spaces of oceans often flummoxed him. What intrigued him were the varying shapes and textures of massed trees and peaks and clustered houses animated by a passing storm or rising sun, rushing water or a full moon. He thrilled in chasing such fleeting moments.

In this, his photos are aesthetic descendants of the dramatic atmospheric effects Albert Bierstadt captured in his paintings of Yosemite in the 1860s. (Bierstadt also took photos on his journeys West.) And Adams conveys a similar romantic notion of a majestic Eden, absent of people and development.

Growing up, he gazed out on a bay empty of the Golden Gate Bridge. But San Francisco went from 343,000 residents in 1900 to 500,000 in 1920. Adams's photos, fueled by new photographic technologies and car travel, are about escaping from this booming new New World. His commercial projects promoting tourism — selling gasoline, amateur photography, and the national parks — invited you to light out with him. He was a pioneer in the use of photos in support of environmental preservation, and he served for 37 years on the board of the Sierra Club. His West is the wide-open, virgin West of California tourist brochures and Hollywood westerns — often photographed from parking lots or close to roads.