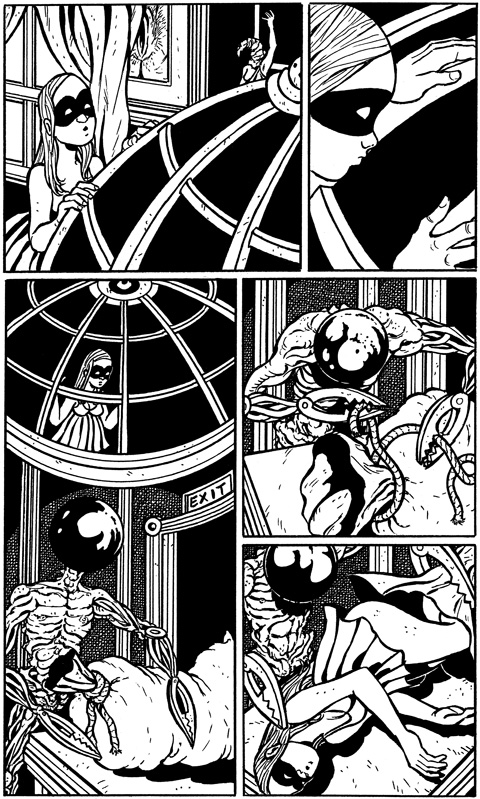

HE CAN'T HELP IT Even if Rickheit's characters aren't doing anything explicit, you know that what's going on can't possibly be innocent. |

I want to have sex with Hans Rickheit. And not just because he once made an autobio comic about autofellatio (isn't that all autobio comics, though, really?). Rather, it's the determined deviance of his works that makes me think he'd be really . . . interesting. . . in bed. Though I might have to ask him not to bring any preserved pig fetuses.

I've been reading Rickheit's comics since the '90s, when they first appeared in Paper Rodeo, the anarchic comix rag published by the late, great Fort Thunder arts collective in Providence. Paper Rodeo was filled with the deeply disturbed, even unmedicated brain droppings of artists like Mat Brinkman and Brian Chippendale, but even so, Rickheit's work stood out. There was something compelling about that bear-faced man slipping into wood-paneled houses only to be confronted with fleshy coin-op chimeras that functioned as pipe organs. Many of the works published in Paper Rodeo back in the day were comics only in the broadest sense of the term — really more like manic scribbles filling the pages — but Rickheit's had all the comics paraphanalia of panels and gutters and sequential progression, which just made them more strange and unsettling.

Rickheit went on to publish two graphic novels, Chloe and The Squirrel Machine, and he's serializing a third, Ectopiary, online. But he has also just released a compendium of his early and uncollected comics in a single disturbing volume from Fantagraphics: Folly. Subtitled "The Consequences of Indiscretion," this book reminded me of why I was instantly fascinated with Rickheit's comics. Here again are the monsters in curio cabinets, the perverted dwarves, the twin masked nymphets fingering each other, that I first fell for.

These comics aren't all that pornographic, but there is a sexuality seeping from everything he draws, more horrifying for its coy implications. It's like that one scene from The Shining with the two furries in the hotel room: they're not doing anything explicit, but by God there's nothing innocent that could possibly be going on there.

|

By happenstance, Folly arrived on my desk along with the latest installment of another cartoonist's foray in the realms of the unreal: The Hive, the second chapter (due out in October from Pantheon) of the hallucinatory saga Charles Burns began with X'd Out. There's a lot in Burns's work that seems to tread the same Cronenbergian territory as Folly: mutated human-like food products, slimy organic machinery, etc. But compared to Rickheit's oeuvre, the perversity in The Hive feels forced. Burns is at his best when he's using the grotesque as a metaphor for the real, as in Black Hole, his high-school mutant-noir novel. In The Hive, it's not clear yet what metaphorical target Burns is aiming at.On the other hand, Rickheit's jointed tentacled biomasses, nestled in their grooved Victorian devices, never seem like a metaphor for anything. They just are.

It's as if other masters of visual bodyhorror — Cronenberg, Burns, Dan Clowes, Tarsem Singh — are weird by choice. Rickheit, it seems, just can't help it. There's a conviction to his creepiness, a compulsive nature even in his early draftsmanship (his current drawings, in their architectural perfection, resemble those of a savant). His work seems completely, horrifyingly honest.

I met Rickheit once, and he was a perfectly pleasant, if shy, fellow. Nonetheless, I can't help wondering what it would be like to get down with a brain that straightforwardly subversive.

Maybe I'd even let him bring the pig fetuses. You never know.