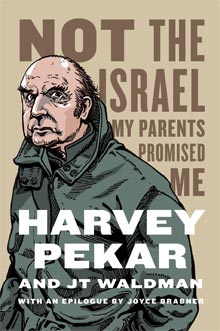

NOT THE ISRAEL MY PARENTS PROMISED ME Pekar's most recent books are linked and inform each other, overlapping like a Venn diagram. |

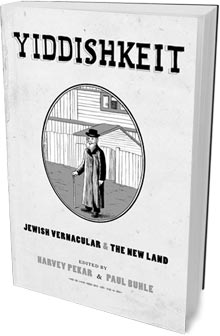

So here's our man, gone these two years and still putting out work. Harvey Pekar was nothing if not a hustler, a working-class autodidact with the most expansive of intellects and the tightest of fists. Before he died in 2010, at the age of 70, he was in what he called retirement, but he was still reading, researching, and writing a slew of comics, trying to make ends meet. One by one, those books have been posthumously printed: Yiddishkeit, a curated anthology of and meditation on Yiddish literature, in September of last year; Harvey Pekar'sCleveland, his ode to his hometown, last spring; and most recently, last month, Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, a treatise on Zionism and its discontents.

Pekar was unusual among artists, in that he was necessary but not sufficient to the work he created. His magnum opus, the autobiographical series AmericanSplendor, is full of ironic, detailed, idiosyncratic observations of unremarkable human lives, and it could not have sprung from any other brain than the one in Pekar's balding dome. Yet it also could not have existed without the artists — more than 70 in all — with whom he collaborated over the years.

I was lucky enough to get to work with Pekar just once, on what became the two-page introduction to Yiddishkeit. When I got the script — a single sheet of 8x11 office paper covered in Pekar's ballpoint-pen handwriting and stick figures — I panicked. I called Dean Haspiel, one of Harvey's frequent collaborators. "There's no way this can all fit on two pages," I said. "I'm not even sure it all makes sense. This is impossible."

Haspiel told me to relax — this was normal operating procedure. My job was to carve a comic out of Pekar's raw script. "You have to take his story and make it yours," he said.

YIDDISHKEIT The anthology is part memoir, part social history, and part text book.

|

So I did. Despite his curmudgeonly reputation, Pekar was more than gracious, accepting some changes to the script and vetoing others. In the end, the published comic — written by Pekar, drawn by me, and inked by the great David Lasky — could not have been produced by any one of us alone. It made me think about the mathematicians David and Gregory Chudnovsky, who attribute their collaborative work to the "Chudnovsky Mathematician" — a third entity that can't be reduced to the sum of its parts. When Harvey died, I wondered: was there a "Pekar Cartoonist"? And if there was, would it live on after Pekar's death?Pekar's three posthumous books are linked and inform one another, overlapping like a Venn diagram. All three contain carefully researched histories, interwoven with memories of Pekar's early years as the child of Jewish immigrants in the aftermath of World War II. They circle around some of the same material, looking at it from different angles, poking it with sticks.