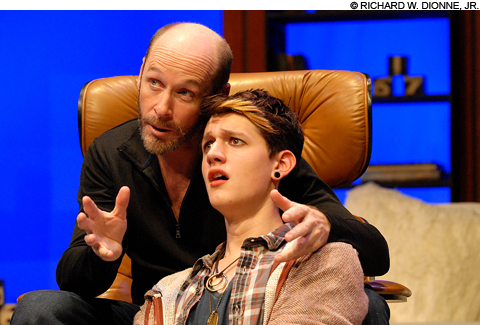

TRAGIC LOVE? Shea and Church. |

Edward Albee has always managed to drill deeply into the human heart and not stop until he gets a gusher, never more so than in The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia? And since 2nd Story Theatre has the habit of taking emotionally precise plays and firing them at us like a sharpshooter, the 2002 Broadway hit will leave audiences reeling as it continues through October 21, deftly directed by Mark Peckham.

The triple-Pulitzer playwright had his work cut out for him. Of course, since The Goat centers around bestiality, he could get by on titillation and reputation. But since the author of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The American Dream demands so much more of himself, the play goes on to capture the elusive essence of love.

After all, in the published version Albee specified a subtitle: "Notes toward a definition of tragedy." And if love in its most excruciating forms isn't a tragedy, nothing is.

When we first get to know them, Martin (Ed Shea) and Stevie (Sharon Carpentier) seem the ideal couple — both smart, with wry senses of humor, doting on each other. Eventually, they both say, and we have no reason to doubt them, that they never considered being unfaithful. Their only annoying habit seems to be correcting each other's grammar and word usage. The single set of the play, designed by Trevor Elliott, is an expansive upper-middle-class living room, complete with tasteful art and lots of little things for Stevie to go around breaking when the jig is up.

It has already been a big week for Martin, his 50th birthday coinciding with receiving the Pritzker prize, architecture's Nobel. His only complaint is his failing memory for little things like names, and the only family "problem" is that their 17-year-old son Billy (Ben Church) has revealed that he is gay — flamboyantly so in this staging — although both militantly tolerant parents agree that it is probably just a phase.

Martin makes the mistake of getting something off his chest to Ross (Mike Zola), his best friend. Rambling through the countryside to find a weekend retreat for him and Stevie, there was this barn, see, this little animal with the most magnetic brown eyes . . . . Ross is understand-ably appalled, and so is Martin, when the next morning his wife receives a letter from Ross that oozes solicitous concern and, betrayal ignored, spills the beans.

Since Albee is a master of his craft, the wife isn't merely a foil for the dramatics of the perpetrator but rather has a fascinating emotional arc of her own. Since they are sophisticated urbanites, she first deals with the situtation by thinking out loud, humor insulating her disturbed concern. She says that a spouse anticipates jolts like "your wife goes dyke" and such, "But cruising livestock?" Stevie tries to control herself, venting by smashing the occasional knickknack as she paces the room. By the controlled way she says she'll kill him — and she says that quite often — we know that Martin's not in that particular danger.

Carpentier is wonderful in the role, walking that knife edge, maintaining balance between the character's fury and restraint, the latter rooted in love, after all. I wanted anguish to peek through now and then, but maybe I'm just too insensitive to have noticed.