PARNOID ANDROIDS: The notion of an entity — good, bad, or indifferent — which unites (or infests) all humanity, persists through Dick’s writing. |

Around the age of 13, Philip K. Dick started having a recurring dream. According to Emmanuel Carrère’s 2005 biography I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey Into the Mind of Philip K. Dick, the future author dreamt that he was poring through a stack of science-fiction magazines, of which he was a huge fan, knowing that when he got to the last story in the very last one, he’d find the secret of the universe.At first he proceeded eagerly, wanting to know. But then he thought, what if the truth is horrible? Immutable? Would he go insane? And so he tried to slow down his search and delay the inevitable glimpse of irrefutable, unbearable knowledge.

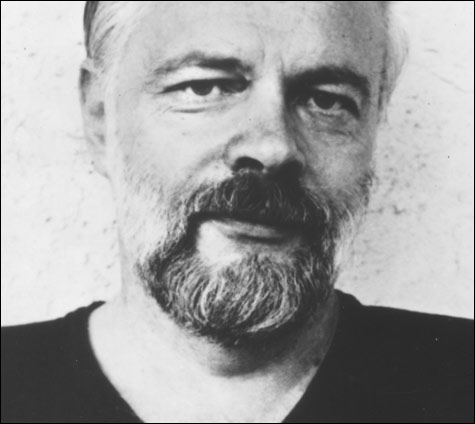

Whether Dick reached that last page by his death on March 2, 1982, is unknown. He did, however, amass his own stack of science fiction, some 40 novels and 100 short stories. At times, according to Carrère, Dick believed that ultimate knowledge lay within his own writings, as have many others since, making him one of the most revered and contemplated writers in the genre. Densely theoretical books have been written about him, several movies have been adapted from his work — some pretty good. Now, in a vindication of sorts, the Library of America has published four of his best novels from the 1960s.

Why the adulation? As a prophet, Dick sucked: flying cars, extraterrestrial colonization, psychics — maybe in alternative futures, but not in this one (he got it right with climate change and celebrity culture, making the environments of his novels oppressive inside and out). His writing was a lot better than scoffers allow, but still uneven. What he did capture with more terror, wit, and assurance than anyone else, however, was the essential paranoia of our age, the nagging suspicion that the official version of reality is a cover-up for a sinister conspiracy. Or divine revelation. Or . . . nothing at all.

For example, in one of the novels included in this volume, 1962’s The Man in the High Castle — maybe his best, and winner of the Hugo Award — doubt arises over the authenticity of the past. The premise of the book makes you wonder why it hasn’t been made into a movie yet: the original Axis of Evil has won World War II; Japan and Germany divide the world, and the US, between them. Maybe Dick’s focus put Hollywood off: the narrative revolves around the sale of fake American antiquities to the Japanese occupiers of the West Coast. Another plot line involves the author of the title and his subversive, banned novel that’s proven a sensation: in that book the Allies have won the war.