|

Will Shakespeare, the 29-year-old playwright and actor, is holed up in the Mermaid Tavern, where he’s writing sonnets rather than plays because it’s 1593 and the London theaters are shut against the raging plague. His rival, Christopher Marlowe, drops by, along with the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s 19-year-old patron. Another frequent visitor is the luscious Emilia Lanier, who tumbles into Shakespeare’s bed but spreads her bounty around, sparking fits of jealousy.

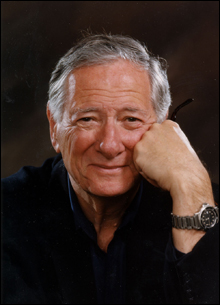

The intrigues among this crew are stuff dreamed up (and researched) by founding American Repertory Theatre artistic director, professor, critic, and playwright Robert Brustein and stuffed into a new drama, The English Channel, which gets its first outing next week at Suffolk University’s newly renovated C. Walsh Theatre. The run there (September 6-15) is followed by one at the Vineyard Playhouse on Martha’s Vineyard. Harvard colleague Stephen Greenblatt’s book Will in the World, which Brustein calls “largely speculation but a beautiful biography,” provided the inspiration for the play. “I was very taken by Steve’s reflections on the evolution of the sonnets and Shakespeare’s relationship to Southampton and the Dark Lady. I saw a play in that.”

| The English Channel | Suffolk University’s C. Walsh Theatre, 55 Temple St, Boston | September 6-15 | $30; $15 seniors, students | 866.811.4111 |

Brustein identifies Lanier as the Dark Lady of the sonnets. “It’s irrefutable, if you think of the coincidences that surround Shakespeare. She was the mistress of Lord Hunsdon, patron of the Globe Theatre, where Shakespeare worked; she was dark and beautiful and a published poet herself.” In the play, Brustein invents a plot line involving a handkerchief given by Shakespeare to Lanier that she claims to have lost, as if to foreshadow the complications of Othello. Shakespeare doesn’t murder Lanier, but he is unforgiving — a trait explored by Brustein in a book in progress, Shakespeare’s Prejudices (Yale University Press). According to the author, the new tome is about what the Bard “had in common with his own time. I’m tracing the misogyny in the plays and especially in the sonnets.”Brustein calls Shakespeare “a big ear,” always copying down snatches of conversation to be used later in his plays. As if in homage to the Bard’s practice of lifting from other sources, Brustein has borrowed from director Andrei Serban’s ART production of Twelfth Night, in which Shakespeare was added as an eavesdropping character, for The English Channel. Brustein believes this image of Shakespeare is “ true of most artists. They don’t have lives of their own. They are sopping up everyone else’s lives like a sponge. You can’t find his personality. He is in his plays, that’s where he lives.”

Although Brustein sees Shakespeare, the man, as unknowable, he is convinced of his genius. At the end of The English Channel, the ghost of the murdered Marlowe returns as Shakespeare’s muse. “It’s something of a thumbing of the nose at all those people who don’t think Shakespeare wrote his plays. There’s enough reference to him in his own time to justify it [his authorship] with complete assurance. My own theory is that educated people don’t like to believe that a person without a college degree can write anything great, which is nonsense. One thing Shakespeare couldn’t do was invent a plot. I sympathize with that.”

On the Web

Suffolk University’s C. Walsh Theatre: www.TheaterMania.com