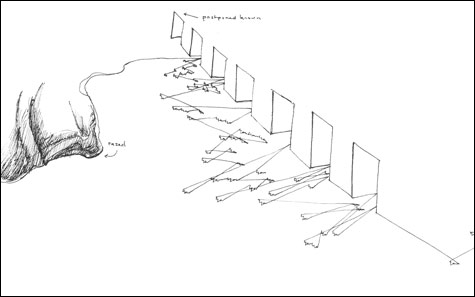

ABSTRACT PASSAGES: One of Daou’s sketchbook drawings. |

The first striking thing about Annabel Daou's exhibit, "Knot," at Brown University's Bell Gallery (64 College Street, Providence, through March 8) is the room itself. The walls, floor, and ceiling are all painted white. This simple gesture threw off my senses — in a good way — and made me think of the hallucinatory white room at the end of the film 2001. The disorientation creeps up on you. In glances out of the corner of my eye, I kept getting momentarily confused between floor and wall, between art and reality.

Daou has covered the walls with fine-line black pen drawings with lots of abstract passages, as well as trompe l'oeil bullet holes, a square hole resembling a grave, hilltops lined with buildings, a flaming chair. It feels like dreamspace, and the visions are unsettling.

Daou, 41, was born and raised in Beirut and has lived in New York since 1999. Asked about the bullet holes, Daou tells me, "I grew up in Lebanon during the war. That was the first 18 years of my life. So it probably comes from that."

The imagery is mainly coded references to literature, her life, her own past art. The flaming chair, for example, is based on an old chair she found in the snow a decade ago and that has occupied her studio ever since. The flames, she says, were inspired by Wallace Stevens's poem "Domination of Black," which speaks of fire and leaves and night that comes "striding like the color of the heavy hemlocks."

The exhibition, which was organized by recently departed Bell curator Vesela Sretenovic, began as a sort of game between Daou and her writer friend David Markus. One by one, he gave her 12 words that she used as prompts for sketchbook drawings (which are on view). The words: aporia, sacrifice, muse, island, place, game, object, trauma, domination, distance, that. At the end, Markus read through her books and responded by writing a long, unpunctuated, poetic sentence (published in the exhibition booklet).

Finally Daou came to Brown and spent 12 days drawing on the gallery walls, developing imagery she previously explored in the sketchbooks. She intends the wall drawing to be one long continuous line. Any time she lifted her pen to pause and then started again, she carefully noted the times on the wall.

I find all these facts about her process tedious, and unenlightening about the final drawing, which is rather more affecting.

Daou starts at the right — Arabic-style — and heads to the left around the room. The first wall is filled with fine tangled lines in which she has spelled out Markus's English sentence phonetically in Arabic — so that it is only intelligible to someone who knows both languages. Asked about this section, Daou speaks of fear of the Arabic language, of loss of meaning, of her bi-national identity.

The next wall includes the cracks and bullet holes, the grave, two poles with a line between them that spans an island, a mountain with the shading made out of the repeated words "stage," "voice," and "truth." The third wall shows houses of cards atop mountaintops. Daou says this is a reference to playing cards in her youth in Lebanon because there wasn't much else to do, as well as a Jean Genet anecdote about Palestinians, forbidden from playing cards, continuing to play in pantomime without cards. It's also a reference to one of her own art projects in which she printed an altered deck of cards.