AMERICAN TRUTHS: Tóibín captures the isolation of the immigrant, the indelible stamp of ethnicity, the incurable homesickness. |

| Brooklyn | By Colm Tóibín | Scribner | 272 pages | $25 |

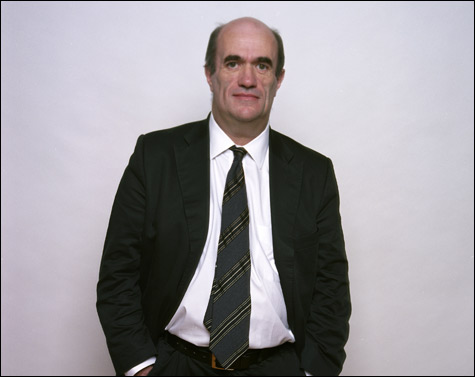

In American prose, there is a plain style, a child of the 20th century, descending from Hemingway and Cather. The best New Yorker writers — James Thurber, Joseph Mitchell, Janet Malcolm — have it. It is homemade and can be found across the spectrum of American writing. Today Paul Auster and Don De Lillo, each in his own way, are masters of this style. In Irish fiction there is a plain style best felt in the novels of John McGahern — his By the Lake is a masterpiece — and Colm Tóibín, who has just published the superb Brooklyn.The power of Tóibín's novels is in their accumulation of simple, clear sentences. The motion forward is deliberate, but it stirs feelings that deepen as it carries you along. Tóibín is a master of the Hemingway dream of leaving something out yet still having it there replete, but not overtly evident, in the prose. As much as I admire and delight in Tóibín's see-through prose, I have not been absorbed by all of his novels. The Master, his last, received high praise, but I did not believe in its version of Henry James and never became engaged. For me, at least, Brooklyn is not only a return to form but also one of Tóibín's best books.

Although set in the early 1950s in Brooklyn, the novel is about deep American truths — the isolation of the immigrant, the painful passage through homesickness to you-can't-go-home-again, the indelible stamp of ethnicity and what it means to be uprooted.

A young Irishwoman, Eilis Lacey, emigrates to Brooklyn's Cobble Hill section, works in a department store, and lives in a boarding house. I will not give away the plot, but I will mention some first-rate scenes: Eilis's crossing by boat, Christmas dinner at the parish hall served up by the priest who sponsors her in America, Eilis's trying on a bathing suit, and her sexual initiation. All the events in the book take place within a world that's barely sketched, a big surround, a blank that she knows is there but does not know by name. Tóibín mentions Jackie Robinson and Pee Wee Reese and you're surprised to register that it is indeed the 1950s, a world a less skilled writer might have felt it necessary to deliver in detail. But Tóibín knows how alone Eilis is, how removed she is from what's around her. When she's nearly crushed by homesickness, you feel it, and when she returns to Ireland, you feel that she's no longer home there, either. So powerful are the undercurrents of this book that the suspense Tóibín creates is real, totally involving.

The richest characters in the book, after Eilis herself, are three older women — Eilis's mother, an employer in Ireland, and the owner of her boarding house. What vivid creatures they are — tart and cutting, kind but armored. Will Eilis be like them when she is older in America? My guess is no. She is shedding her Irishness as, indeed, Brooklyn has. On Flatbush Avenue as it runs up to Prospect Park, there were once scores of Irish pubs. Now there are one or two. Eilis will become American. Which means, in this novel, one who has suffered through and been, perhaps, annealed by great loss.