.jpg)

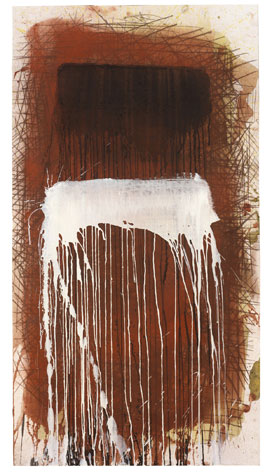

FLUIDITY The Austria Group, No 2. |

The wreckage at the end of Modernist art's main thrust is the starting point for "Pat Steir: Drawing Out of Line," a four-decade retrospective of the New Yorker's drawings at the RISD Museum (224 Benefit Street, Providence, through July 3). Modernism's drive to break art down to its essential, atomic, abstract elements climaxed in the '60s with Minimalism's all-white paintings and giant steel cubes and then Conceptual art's dematerialization of art altogether. Steir is part of a generation of artists who, beginning in the '70s, struggled to pick up the pieces and reverse engineer art again.

Steir's early efforts are often awkward and at times tedious, but RISD curator Jan Howard — who helped organize Steir's last major drawing and print retrospective at the University of Kansas in 1983 — and independent curator Susan Harris assemble them into a sharp, scholarly show, one of the best of the year. And about two-thirds of the way through, it explodes into ravishing beauty.

Works from the 1970s in "Drawing Out of Line" show Steir cataloging the elements of art — scribbles and scrawls, ruled lines and curves, dashes and dots, smudges, words, charts, illusionistic renderings of a squid or a fighter plane or an orchid. These various elements and styles are rendered one next to the other in single drawings, often organized around a framework of rectangles and grids. It's like collecting all the vocabulary of a lost language before trying to speak it again.

Suddenly in 1985 and '86, these semiotic directories of small marks transform into 14-foot-wide drawings of crashing waves, which for Steir symbolized her overwhelming grief over the death of her mother at that time. They're uneasily balanced between studies of the language of markmaking — the waves are built from sweeping charcoal lines, the arc of the reach of her arm — and illusionistic pictures. Art thinking still trumps and resists feeling. But the larger scale of the marks and their vigorous, cascading repetition gives the drawings a new kinetic energy.

RAPTUROUS February Series, II. |

The show's focus on drawing may give a misimpression of the progression of Steir's art by skipping her early '80s flower paintings, which are divided into grids in which each panel samples a different historical style. Then came the wave drawings and paintings, which evolved into her celebrated waterfall paintings around '87, earlier than the drawings here might suggest.

That transition is marked here in After Sao Paolo, from about 1990, when after years drawing primarily in pencil, charcoal, pen, Steir switches to ink and gouache. These water-based media, applied with wide brushes, add a new fluidity to her drawings. She fills the 21-foot-wide paper with broad horizontal brushstrokes, like veils of black (and here and there semi-opaque white). Minimalist grids that had been a staple of her work become more casual stacks of rectangular brushstrokes. The bottom edge of each stroke delicately drips down the paper, across all the strokes below. This growing looseness and airiness, inspired by studies of traditional Asian drawing and calligraphy in China and Japan, creates a new romantic mood.