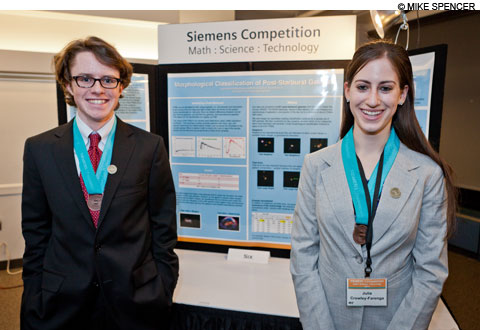

MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE High schoolers Julia Crowley-Farenga and Patrick Loftus beat out projects on DNA and nanotech with their astronomy research. |

When I met them, Julia Crowley-Farenga and Patrick Loftus were hanging out in front of their science project, "Morphological Classification of Post-Starburst Galaxies."They were dressed super cute — Crowley-Farenga wore a navy-blue crested cardigan and blingy earrings; Loftus, a pair of salmon-colored skinny jeans, a blue floral button-down, and blue canvas kicks. "We looked at 2811 galaxies," Loftus said, "and for them we developed a visual classification system in order to further investigate and understand the evolution of galaxies in the universe."

Studying their movement, he continued, will ultimately determine the fate of the universe.

Yes, the fate of the universe. Unlike the shoebox dioramas and model volcanoes that dominated the science fairs I attended as a Precambrian high-school student, last week's regional finals of the national Siemens high school science competition was markedly more sophisticated.

DNA translocation, nanotechnology, and cutting-edge astrophysics were among the disciplines represented on the text-heavy particle-board triptychs, which these kids had lugged to the third floor of the MIT student center in Cambridge from their hometowns all over the country.

Five individuals and five two-person teams were competing for a substantial amount of scholarship money. On Saturday, Crowley-Farenga and Loftus would win in the team category for this round, taking home $3000 each and getting the chance to compete for the $100,000 grand prize at the finals, to be held next month in Washington, DC.

"It took me so long to do this," said Crowley-Farenga, who, like Loftus, is a senior from Evanston, Illinois. "For the majority of the summer, I was looking at pictures of galaxies for three or four hours every morning."

"We were looking for characteristics that indicated important events in their future or their past," Loftus added.

"Some of the previous research we looked at used four classification systems," Crowley-Farenga said. "We used 56." Their research represented what Loftus calls a big step in a new field. "Our mentor called the research of post-starburst galaxies a trendy, hipster sort of thing," he said.

Nearby, the John Solder — a tall, preppy senior in khakis from Westport, Connecticut, who would go on to win in the individual category — hovered in front of a poster with pictures of colorful brain scans whose patterns resembled a Missoni knit.

"The simple, condensed version of my project would be that I researched a new optogenetic method engineered to treat disorders in the cerebral cortex of the brain," Solder told me. He had determined a way to use light and genetic therapy to target a highly specific set of neurons that, if damaged, cause a host of problems. He developed his own computer programs to test his methods.

"I think optogenetics is the future," Solder said. After discovering the field through his own research, Solder approached a Yale scientist to be his mentor. He agreed, and this summer Solder worked full-time as an unpaid intern in a genetics lab. He would have preferred to earn money, but he remains optimistic.

"I'll get paid for something someday," he said.