CUCKOO. The Clock is not just telling time, but is telling us about time, and film as well. |

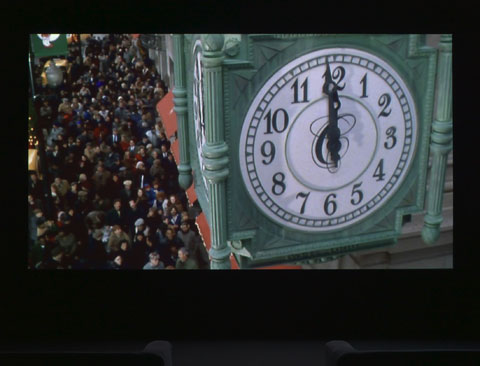

In one of many famous scenes in Carol Reed's The Third Man (1949), Harry Lime, played by Orson Welles, discusses conflict and history. "In Switzerland they had brotherly love," he says. "They had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock."I can't help thinking of that remark after taking in the 9 pm to 12:30 am shift of Christian Marclay's 24-hour-long tour de force, The Clock, which is not to be confused with Vincente Minnelli's 1945 romance of the same title (although a snippet from that does appear at the 12:05 am mark). Marclay (who is, perhaps irrelevantly, half-Swiss) has put together bits from thousands of films, all featuring some chronometric source showing the exact time, synchronized with the real-life time where the work is being screened. He may have built the greatest cuckoo clock ever.

And what's wrong with that? It's not just fascinating and ingenious, but it also has a practical function. People are talking about turning the film into an app. How cool would it be to check the time at around 9:20 pm on your iPhone and have, say, The Time Machine (1960) pop up. Or Time After Time (1979) an hour later.

But more than being a gimmick or a more grandiose version of Life in a Day, The Clock is not just telling time, but is telling us about time, and film as well. For example, who knew there were, well, so many different kinds of clocks and watches and other timepieces in movies?

To be more picky, why are there so many scenes in the Roger Moore 007 films in which Bond looks at his watch before, after, or while having sex?

And it seems not a minute goes by, at least in the chunk of the film that I saw, without a shot of someone lying in bed next to a clock radio who is suddenly disturbed by a phone call.

Phone calls in general are a recurrent motif in The Clock (in 1995 Marclay made a seven-minute short on the subject called "Telephones"). The film repeatedly cuts from someone dialing a phone to someone answering the phone in a different movie, often with amusing results.

This is just one instance of Marclay's exploitation of that basic principle of cinema, the Kuleshov effect — the tendency for viewers confronted by two disparate pieces of film edited together to fill in the gap with a story, often shaped by the conventions of similar films that they already have seen. This usually happens unconsciously, but Marclay stimulates this response over and over again, frustrating the desire for resolution, and forcing the viewer to recognize the illusion of narrative — both in movies and in real life.

As such, I can see The Clock paired in the double bill from hell with Douglas Gordon's 1993 installation 24 Hour Psycho, in which Hitchcock's iconic thriller is stretched from the original 109 minutes to the title length. Instead of filling the moment with a barrage of shots as in The Clock, 24 Hour Psycho prolongs it to mystic lengths. I haven't seen it, but after reading Don DeLillo's description in his novel Point Omega, I'm not eager to try.