DOCU-DRAMATIST: Michael Winterbottom’s latest film, A Mighty Heart, is the story of Daniel Pearl, the American Wall Street Journal reporter who was kidnapped and killed by Islamic extremists. |

We’ll get used to it, I suppose, this new category of moviegoing distress. Sooner or later, we get used to everything.But for now, watching the passengers bustle toward the gate at Newark on the crystalline morning of September 11, 2001, in Paul Greengrass’s United 93 (2006), or hearing Daniel Pearl chat happily to his Karachi cab driver in Michael Winterbottom’s A Mighty Heart, we find ourselves — in the immunology of anxiety — at the mercy of an entirely fresh strain. We know that the plane, after much struggle, will become a hecatomb in a field in Pennsylvania, and we know that the reporter from the Wall Street Journal will be abducted and then decapitated. We know all this, yet foreknowledge offers no defense; a different sense of possibility is at work here, one in which our unease feels limitless. Heaven gapes over Newark; Karachi hisses and sprawls around Daniel Pearl. There will be no closure on these events that we can foresee: history, awoken with a thunderclap on 9/11, is not about to put itself back to sleep.

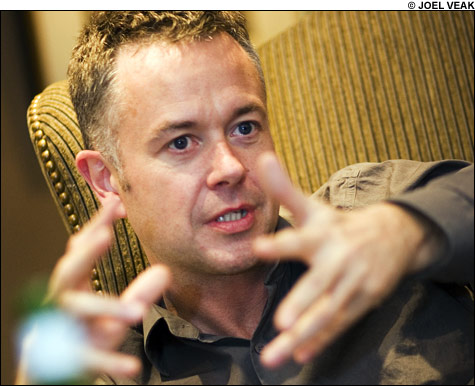

“If you’re filming in a normal way,” says Winterbottom, curled around a glass of mineral water in a room at the Eliot Hotel, “the kind of conversation you keep having is, ‘What does this mean? Where does it fit in? How does it connect with what went before?’ But I’m more interested in the moment itself, rather than its relationship to the moments around it. Because, in reality, something happens and then it’s followed by something completely different, with a completely different set of reactions. Continuity is not the main thing, if you know what I mean.”

It is Winterbottom’s head for the discontinuous that has fitted him for the job of quintessential post-9/11 filmmaker.

Reality itself at stake

A Mighty Heart is Winterbottom’s third film to be set recognizably in a world in which the Twin Towers have fallen, in which continuity has been broken and the protagonists are obliged to deal with the switchbacks and mood disorders of a radical new reality. The first, In This World (2002) followed the progress of two young Afghans from their refugee camp in Peshawar, on the Pakistani frontier, as they moved illegally through Iran, Turkey, and into Europe, en route to a destination in London. The journey — wintry mountain passes, stifling industrial containers — is real (Winterbottom made it himself before returning to Peshawar to reconnect with his cast), the dialogue is unscripted, the two leads are playing themselves. Only the situations in which they find themselves are to some degree engineered. “We couldn’t tell them what to say, culturally or linguistically or whatever,” says Winterbottom. “So we’d set up the situation, the bus journey or getting stopped somewhere, and they’d just respond to it as it happened. It was a hands-off approach, almost like an observational film, because that seemed to me to be the only way [there was] of getting it right and accurate from their point of view. It was in their hands, really.”