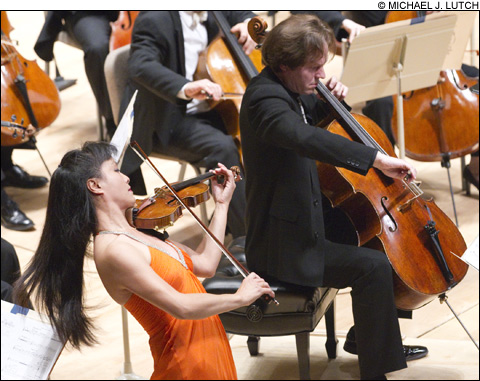

A “COMPANIONABLE MARRIAGE” Mira Wang and Jan Vogler were the superb soloists in John Harbison’s Double Concerto — and they just happen to be married to each other. |

Outpourings of love have been flooding the Boston musical scene. Colleagues, friends, students (among them students from Venezuela’s El Sistema), and admirers of the late Marylou Speaker Churchill (former principal second-violinist of the BSO) — from brilliant young pre-school performers to Yo-Yo Ma — overflowed the Jordan Hall stage and house back on April 4. Everyone spoke about her joy in, and dedication to, music, and everyone who performed partook of that joy. She herself had the last soul-stirring word in a recording, with pianist Veronica Jochum, of the transcendent last movement of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps.

More love was directed at pianist Russell Sherman, who’s celebrating his 80th birthday in a series of Haydn/Schoenberg recitals at Emmanuel Church. (The final one is this Sunday, April 25.) His musical insight has grown deeper and more complex over the years, if on occasion he’s less technically steady. (Haydn spotlights even the smallest imperfection.) Sherman emphasized Haydn’s great minor-key poignance, and also the underlying seriousness of his game playing, and then Schoenberg’s seriousness and the game playing behind that. Sherman’s conceptions and his playing have a new fullness, and at his very best, especially throughout the second concert, that fullness fills the listener.

At that second concert, he turned over Haydn’s B-minor Sonata and Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Piano (Opus 23) to Katherine Chi, one of his most gifted former students. She played the Haydn with heartbreaking elegance and the Schoenberg with the clarity and playfulness you’d expect in Haydn, plus an added sense of urgency.

Emmanuel’s Haydn and Schoenberg year closed with “Reinventing Vienna,” this final concert led by John Harbison as Emmanuel’s acting artistic director and Michael Beattie as associate conductor — a spine-tingling event that also became something of a love-in. Beattie led the small Emmanuel Orchestra in Schoenberg’s hallucinatory Accompaniment to a Cinematographic Scene (1930) — imaginary film music that seems like an entire Mahler symphony, full of waltzes (very Viennese) and menace, compressed — collapsed — into 10 minutes. Then he returned with soloists Danielle Maddon (violin), Rafael Popper-Keizer (cello), Peggy Pearson (eloquent oboe), and Thomas Stephenson (burbly bassoon) in one of Haydn’s rare concertos, the charming B-flat Symphonia concertante.

After intermission, Harbison led a transparent performance of Schoenberg’s landmark Five Pieces for Orchestra (1909), in the composer’s uncannily beautiful chamber version. You could hear every mysterious strand — sudden dramatic shifts in one movement, otherworldly stasis in another. He’s taught at least one audience in town to love Schoenberg. He closed with the vivacious and virtually unknown Symphony No. 70, in D major and minor, with its canons going in opposite directions, its vigorous “hunting” Minuet interrupted by a heavenly pastoral Trio, and, in the Allegro con brio Finale, knock-the-breath-out-of-you surprises.

At the BSO, love (and some anger) was directed at its absent music director, James Levine, as he prepared to undergo further back surgery. The Globe and the New York Times have raised a firestorm of speculation about whether Levine will return. Most of his admirers devoutly hope so. He’s transformed the orchestra’s playing and put programming on an exciting new track. He’s not replaceable. I wish him the speediest and, more important, the fullest possible recovery.