STILL DESPERATE “We were alienating people in terms of what they expected from rock music in 1980,” says John Doe. “The mainstream was really soft and had forgotten what rock and roll was supposed to be about.” |

For a movement that was rooted in a deep hatred for everything that had become plastic and tame about youth culture, punk rock was supposed to be about the music before anything else. Yet when people today think back to the early days of the seminal Los Angeles punk band X — a group defined by the lyrics of their stark hymns to their own California dream (and nightmare) — the first thing that probably comes to mind are the tiger-striped bangs of the fantastically-named Exene Cervenka. After that, we remember the caterwauling close vocal harmonies that she created with a quietly handsome, denim-clad bassist named John Doe.X were as no-bullshit and anti-commercial as they come; what's more, the decade's first couple of punk (married from 1980 to 1985) were a yin-yang comprising exotic otherness and everyman grit. But neither came to the music world baptized as such. When Doe (born John Nommensen) and Cervenka (born Christine Cervenka) formed X in the late '70s with guitarist Billy Zoom and drummer DJ Bonebrake, it was their love of poetry — and not their look — that set them apart from their peers. "I know [poetry] was important to Exene and I, and it definitely gave us a connection to the Doors — whose Ray Manzarek would produce the first four X LPs — and to other so-called poets in rock," noted Doe by phone last week from a hotel in Mexico City.

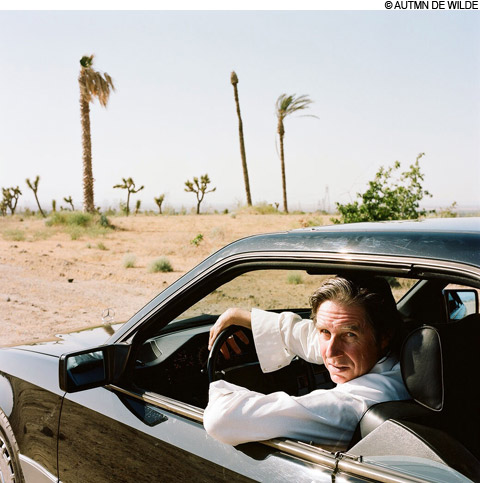

The combination of poetry and punk wasn't for everybody. Doe, who plays Brighton Music Hall on Monday, recalls that the stalwart Zoom tolerated Doe and Cervenka's lyrics (such as the somber themes in 1982's Under the Big Black Sun), though it certainly wasn't his favorite part of being in the band. But as punk fans have come to look past the iconic vacantness of Sid Vicious's sneer, they can now see that punk was never really about being a "punk" as much as it was about thinking. And for poets who could also sing, such as John Doe, Patti Smith, Richard Hell, and Tom Verlaine, punk offered a much needed intellectual refuge from the excesses of '70s pop music.

Where New York's '70s punk scene was full of bands with pop-art names that conjured cartoons and camp (e.g., Blondie, the Ramones, the New York Dolls), Los Angeles was rife with bands whose names reeked of alienation from the cocaine snow job of Hollywood's clubland. Bands like the Germs, the Weirdos, the Zeros, and X were not only rebelling against the music establishment in general, but also against the looming behemoth of the city's entertainment industry.

"X wasn't Flipper or Sonic Youth or anything that was purposely obscure," says Doe. "But we were alienating people in terms of what they expected from rock music in 1980. What they expected of music was either Linda Ronstadt, or the Eagles, or Ted Nugent. The mainstream was really soft and had forgotten what rock and roll was supposed to be about: freedom, youth, aggression, and just sort of being in your face."