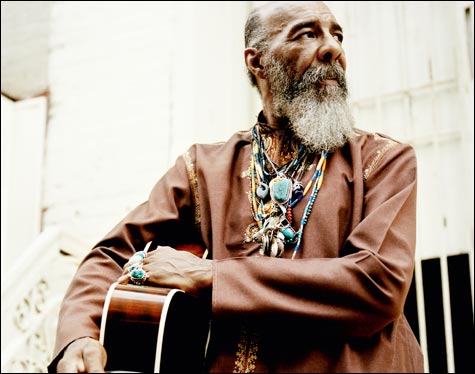

HOLD YOUR NOTES: “I don’t really record a record. I perform it. So I don’t have to sing a tune 20 times because of some producer’s ear.” |

It's a stirring piece of footage: near the beginning of Michael Wadleigh's film of the 1969 Woodstock festival, a bearded man in an orange robe walks up, already furiously strumming his guitar as he nears the center-stage stool. It isn't dark yet, and chaos surrounds him as people are still pouring in and staff are frantic. He sits down and plows through a riveting version of the anti-war screed "Handsome Johnny," his thumb-over-the-neck strumming working up an intense head of steam. Although the song ends, he keeps chugging, slowly building another manic foundation. This time, he opens his mouth and repeats one word, over and over: "Freedom." The song is completely improvised, and every time I see this clip, I'm overcome by the way Richie Havens allows the music to overtake him, even amid all the distractions. What was it like to step on stage and walk off the cliff into the unknown?

"I'd been put on the spot before, but that time I put myself on the spot, you know?" says Havens in his instantly recognizable baritone. "When I go on stage, I usually know the first and last songs that I'm gonna do, but the rest is open space! I tune my guitar between songs, a song comes to me, and I'll sing that. I follow the music to the stage."

Havens, who comes to the MFA this Sunday, has been following his muse since he was a child. He started out singing in various doo-wop groups in Brooklyn in the '50s, only to gravitate to the burgeoning countercultural Greenwich Village folk scene of the early '60s, a move that would lead to his opening slot at Woodstock. "I was 19 when I started [singing doo-wop]. And you know, doo-wop was show business, right? But little did we really know that among the love songs, there were songs of protest, like the songs I'd hear years later. For instance, Frankie Lymon sang 'Why Do Fools Fall in Love?' — good question, right? But he also sang this song: 'No no no no no, I'm not a juvenile delinquent!' Now how about that in the 1950s?"

Still, it was an eye-opening experience for Havens when a trip to Greenwich Village in 1961 revealed a completely new world of poetry, music, and meaning. "The older guys in the neighborhood [in Brooklyn], they were all calling us 'beatniks.' Me and my partners were all like, 'What the hell is a beatnik?' We're still singing doo-wop on the corner, right? So then my friend comes to me two or three days later and says, 'See that guy over there, with that hat — he's a beatnik! And there's more in the Village!' And I said, 'Oh, okay, let's go see who "we" are!' So we went over there and we found the poets. So those older guys, they were trying to be inflammatory, but they were helping us out — it was the best thing that ever happened to us!"