A SNAGGLE OF CONTRADICTIONS Mark Wigglesworth's Mahler Fourth was fresher than his Beethoven but not more profound, and in the finale Juliane Banse was small-voiced. |

Last week's Boston Symphony concert was a snaggle of contradictions. British guest conductor Mark Wigglesworth was substituting for the exciting but erratic Russian maestro Yuri Termirkanov, who'd cancelled all his American appearances. Two weeks earlier, the BSO had announced that in Beethoven's Violin Concerto, German violinist Isabelle Faust would replace the hot young violinist Julia Fischer, who cancelled "for personal reasons." Faust made her BSO debut a bit over a year ago, and I was impressed with her warm, viola-like sound in the Berg Chamber Symphony (pianist Peter Serkin also played). But this time, with her fine, vibratoless tone, the temperature dropped considerably.

The concerto begins with a series of (ominous?) drum taps and a mysteriously inviting oboe phrase. All the principal orchestral parts were here taken by second-desk players, several of whom are among my favorite BSO musicians. But Keisuke Wakao's coarse, expressionless oboe playing was less than inviting. Was Wigglesworth trying for that kind of performance? No — if anything, he depersonalized every possibility of emotive expression to the point of refined blandness, which Faust's pretty but small-scale metronomic playing merely seconded.

She, at least, had a few moments of interest. She played her own transcription of the first-movement cadenza that Beethoven conceived for his piano version of the violin concerto (!), which includes a duet with the timpani. This decidedly militarizes the cadenza. Some of her slow phrasing in the opening Allegro movement was more compelling than her fast playing. Did this mean the slow second movement was going to be even better? No — it was actually less imaginative, had even less feeling. Faust likes to incorporate historical performance techniques, but she was so neutral, her playing seemed empty rather than intimate. She sounds nice, though, and she was rewarded with a surprisingly warm ovation.

The BSO sprang to life in Wigglesworth's fresher, if not more profound, approach to Mahler's Fourth Symphony. Mahler's orchestra is like the world's largest chamber orchestra, with myriad solos rather than thick-textured sonorities, and the BSO — its first-desk players back in place — reveled in the opportunity: John Ferrillo's poignant oboe, William R. Hudgins's teasing clarinet, Richard Svoboda's warm (not comic) bassoon, James Sommerville's full-throated, characterful French horn, Richard Sheena's eloquent English horn, Ann Hobson Pilot's plucked harp combining with unison pizzicato basses. Elizabeth Rowe's magic flute perhaps sounded more urbane than pastoral, and concertmaster Malcolm Lowe's beautiful violin playing may have been too beautiful for the second movement's insinuating Dance of Death. (Mahler wants the violin tuned a step higher to make it sound like country fiddling.)

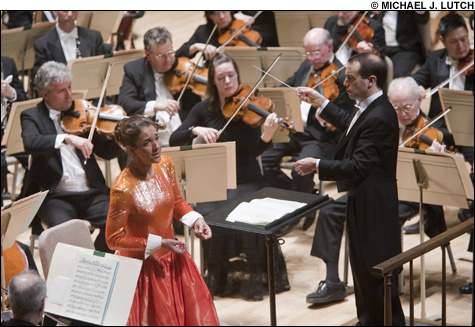

In the last movement, an angelic soprano welcomes us into Heaven, where she enchantingly describes the daily chores (nice that the houselights rose subtly so we could read the text without eyestrain). The German/Swiss soprano Juliane Banse's smallish voice was sometimes hard to hear, and her German diction was unexpectedly imprecise. Her odd, unsettled timbre seemed too dark for this child's-eye view of Heaven. She's a trained dancer, though, and it was touching to watch her swaying to the music as she sat listening to the three movements that preceded her singing.