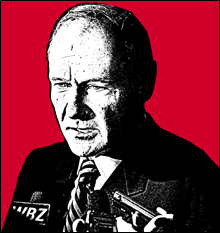

Forget about whether Attorney General Tom Reilly did the right thing. The question now is whether his candidacy for governor is damaged goods.

Forget about whether Attorney General Tom Reilly did the right thing. The question now is whether his candidacy for governor is damaged goods.

If you watch TV or read the newspaper or listen to the radio, you know that the would-be Democratic nominee starred in a political mini-scandal earlier this month. The flap centered on a November call Reilly made to John Conte, the Worcester County district attorney, about a one-car accident that killed Southborough teens Shauna and Meghan Murphy back in October. Reilly reminded Conte that, according to state law, the Murphy sisters’ medical records — which may show they were drinking the night their vehicle crashed into a utility poll — shouldn’t be released to the press.

Taken in isolation, this call might have been unremarkable, if a bit unnecessary. (After all, does a district attorney really need to be reminded to follow the law?) But certain details complicated the situation. The sisters’ parents know Reilly personally. Mark Leahy, the Northborough police chief, publicly questioned the Worcester DA’s decision not to press charges in connection with the case (against the person at whose home the girls may have been drinking). And Reilly contacted Conte after receiving a call from Lycos founder Bob Davis — who, in addition to being the Murphys’ neighbor and serving as their spokesman after the fatal crash, hosted a June 2005 fundraiser that raked in $14,000 for the AG. (Christopher Murphy, the girls’ father, donated $300 to Reilly’s campaign at that event.)

Ask a Massachusetts Democrat, and they’ll insist that Reilly did nothing wrong. Frank Bellotti — himself a former attorney general and candidate for governor — notes that Massachusetts law instructs attorneys general to “consult with and advise district attorneys in matters relating to their duties.” “When I was in office, we used to have contact with them almost on a daily basis,” Bellotti says. Meanwhile, former governor Mike Dukakis argues that Reilly’s call was less problematic than a questionable tax break received by the husband of Kerry Healey, the lieutenant governor and front-runner for the GOP nomination. “I don’t think it compares with million-dollar tax breaks for moving a company to Beverly Farms,” Dukakis says. “Do you?”

Reasonable points, both. And indeed, later developments gave Reilly a measure of vindication. The Northborough police chief apparently backed off his claim that the Worcester DA’s office refused to hand over the girls’ medical records, for example. And the assistant DA in charge of the case said that he had no knowledge of Reilly’s call when he recommended against bringing charges in the case. The good news, for Reilly and his supporters, is that the episode finally seems to have played itself out.

Now the bad news: when the 2006 Massachusetts governor’s race comes to a close, January may be remembered as the month when Reilly’s carefully crafted persona — that of a tough, competent, squeaky-clean public servant capable of breaking the Republican monopoly on the governor’s office — started to unravel.