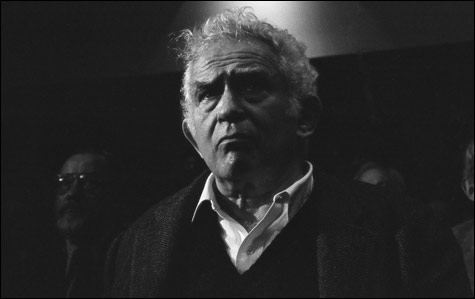

THE TIME OF HIS TIME: Mailer seems so brave precisely because he was so ready to risk looking foolish. |

| Miami and the Siege of Chicago | By Norman Mailer | New York Review of Books | 241 pages | $14.95 [paper] |

“We will be fighting for forty years.” Reading those words at the end of Norman Mailer’s 1968 Miami and the Siege of Chicago, you can’t help but feel a chill. At that year’s political conventions, the GOP performed its Lazarus act on Richard Nixon’s political career in Miami and the Democrats appointed Hubert Humphrey as the public face of their self-destruction in Chicago while, in the streets outside, Mayor Daley’s storm troopers brutalized protesters and anyone else in their path. These were socio-political events begging for the exegesis that Mailer, that dogged visionary, could bring them. Wrong as often as he was right, Mailer seems so brave precisely because he was so ready to risk looking foolish.In Miami and the Siege of Chicago, which he wrote on assignment for Harper’s, Mailer was not only perfectly attuned to the moment but prescient. The 40 years he foresaw were, he understood, years in which Nixon’s reign of law and order — the appeal to middle-class “forgotten Americans” — represented an end to the sober, careful conservatism that had always ruled the Republican party and the beginning of something more sinister, something whose logical endpoint is the radical right epitomized by George W. Bush. It’s a period that may now be coming to an end as the Republicans, like a cancer that turns on the good cells first, are destroying themselves after nearly destroying the country.

It’s in that context that a potentially unifying figure like Nelson Rockefeller had no chance to win his party’s nomination. And though Mailer says that considering Reagan for the office of president would be like imagining Johnny Carson in the job, he perceives the 57-year-old Reagan as the GOP’s equivalent of the rising young man waiting in the wings. “He had the presence of a man of thirty,” Mailer writes, “the deferential enthusiasm, the bright but dependably unoriginal mind, of a sales manager promoted for his ability over men older than himself.”

Mailer is just as unsparing of the Democrats. Theirs is a convention haunted by absences — that of LBJ, so unpopular he didn’t appear and was barely mentioned, and Bobby Kennedy, shot two months earlier as he seemed to be closing in on the nomination. Before Mailer gets to the carnage perpetrated by the Chicago police (much of the detail provided by long quotes from the reporting of Steve Lerner in the Village Voice), there’s a section that could read as a forecast of every weak-kneed Democratic folly to come. His description of a rally for Eugene McCarthy locates McCarthy’s appeal as combining the most ascetic elements of the academy and the priesthood. His observation that McCarthy’s keen righteous anger lacks “that sense of property which is the fundament of all political relations” reads now like a warning about the prissy refusal to engage in the messy business of political horse trading — a perpetual Achilles’ heel of the left.

For all its prescience, this book is also a throwback. As Frank Rich points out in his new introduction, no magazine or newspaper is assigning the type of literary reportage Mailer does here, the sort that Hunter S. Thompson would do in 1972, or that the novelist/critic Steve Erickson would do in his books Leap Year and American Nomad. In 1968, Esquire’s correspondents in Chicago were William S. Burroughs, Terry Southern, and Jean Genet. The very possible election of Barack Obama would bring some sort of arrest to the worst impulses of the republic that Mailer sees gaining momentum here. The fight for journalism goes on.

Topics

Topics:

Books

, Barack Obama, Eugene McCarthy, Frank Rich, More  , Barack Obama, Eugene McCarthy, Frank Rich, George W. Bush, Hubert Humphrey, Hunter S. Thompson, Jean Genet, Johnny Carson, Nelson A. Rockefeller, Norman Mailer, Less

, Barack Obama, Eugene McCarthy, Frank Rich, George W. Bush, Hubert Humphrey, Hunter S. Thompson, Jean Genet, Johnny Carson, Nelson A. Rockefeller, Norman Mailer, Less