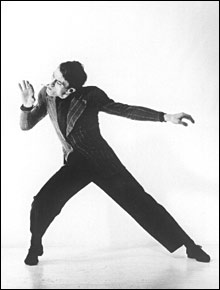

STRANGE HERO: In memorable solos Nagrin portrayed tough, wary, man-in-the-street characters. |

Daniel Nagrin was one of the last surviving stars of modern dance's second generation. He studied with all the greats: Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Anna Sokolow, Hanya Holm, and his first wife, Helen Tamiris. By the time he died, on 29 December in Tempe, Arizona, he'd reinvented himself several times, as a dancer/choreographer, company leader, writer, and master teacher.Born in New York City, Nagrin started his career in the 1940s, straddling modern dance and Broadway. He was featured in several shows choreographed by Tamiris, among them Annie Get Your Gun and Up in Central Park, and together they formed a concert-dance company that gave "serious" performances in between their commercial projects. It was unusual at the time for modern dancers to invest their efforts in the popular stage, but Nagrin was open to opportunities wherever they lay.

In the 1940s and '50s, along with contemporaries like Gene Kelly and Josû Limón, Nagrin fought against the stigmatized image of male dancing. In memorable solos he portrayed tough, wary, man-in-the-street characters — Strange Hero, Man of Action, Indeterminate Figure. He deployed a high-powered technique and performing style to create these macho types who betrayed their vulnerabilities. For years he toured the country with solo programs; that culminated in the complex, evening-length performance piece The Peloponnesian War (1968).

Through Tamiris, Nagrin had studied acting and taught movement for actors. By the time the countercultural '60s arrived, he was looking for a dance analogue to the work of theater directors like Joe Chaikin and Jerzy Grotowski. He wanted to open the way for personal expressiveness, to knock down the wall, as he said, between the act of dancing and the work of acting.

Divorced from Tamiris in 1964, Nagrin re-established himself in a SoHo loft and began working on structured improvisation techniques for dancers. The Workgroup (1969–1974) announced its intention to "explore the possibilities of interactive improvisation and to develop the forms and skills to perform improvisation for the concertgoing audience." The books that came out of those years, How To Dance Forever (1988), Dance and the Specific Image (1994), The Six Questions (1997), and Choreography and the Specific Image (2001), are filled with exercises, games, and structures for exploring the performance process, and they're still gold mines of material for movement work.

When the Workgroup disbanded, Nagrin returned to solo performing, gradually adapting the intensive workshop process for short-term teaching situations as he toured. He never relinquished the "expectation of deep personal involvement" from the participants.

Like most independent dancers, Daniel Nagrin was an accomplished teacher. In 1982 he joined the dance faculty of Arizona State University, from which he retired as an emeritus professor in 1992. He continued to be in demand as a guest teacher. His wife, artist and illustrator Phyllis Steele Nagrin, accompanied his latter-day travels with sketchpad in hand.

In 2004 and 2006 he taught awestruck students at Concord Academy Summer Stages. According to Summer Stages directors Amy Spencer and Richard Colton: "All who met him, or saw him dance, are closer to understanding the essence of the art. He lived with incredible discipline yet with passion. This was evident in every phrase he danced, every class he taught, every improvisation he led. His ceaseless creative flame — which could, we all know, on occasion burn — lit a path for dancers and actors to become more deeply themselves, to become artists. He will always be just over our shoulder: a giant, a source of Promethean energy."

After he retired from dancing, in 1981, Nagrin taught some of his solos to young dancers, but they never captured the edginess and urban energy of his own performances. On stage he was tense, jazzy, confrontational, a wiseguy, an insomniac, a risk taker. In class or in conversation you could feel his curiosity and his concern for you, once you got past being intimidated by that gimlet gaze of his. He was probing, always probing for the depth of experience, yours and his own.