LA PUERTA ABIERTA: Tracing the woman's inner journey. |

World Music's Flamenco Festival featured women dancers this year, with a single performance of Isabel Bayón's La puerta abierta ("The Open Door") and three shows by Soledad Barrio and Noche Flamenca at the Cutler Majestic. Bayón played an eternal feminine archetype, surrounding herself with proud, seductive gestures. Barrio was herself, dancing here and now for dear life.Within an austere theatrical framework Isabel Bayón arranged traditional flamenco forms to trace the woman's inner journey. Very slowly the lights come up on a woman revolving in a void, with a man's voice that seems to be issuing from a faraway cave, wailing the siren song of memory. The woman stamps and curls her arms and stares sharply in all directions, looking out into the dark. A recorded pianist plays one of the more introspective of Bach's Goldberg Variations. The woman dances the music, gesturing or turning on every note.

Finally, with five musicians seated to one side, she moves upstage to a room suggested by simple black drapes open in front of a white wall. The woman withdraws to this space and meditates while the musicians play and sing. (Miguel Ortega was the anguished singer, with Jesús Torres on guitar, Antonio Coronel on percussion, and Luis Peña and Carlos Grilo as clappers.)

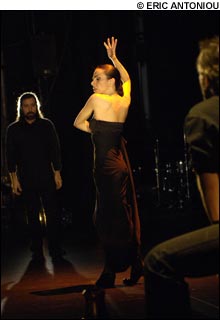

During each musical interlude Bayón changes clothes, each costume representing a different frame of mind or stage of her life and affording her a motive for dancing. There's a flamenco gown with a voluminous ruffled train, a silk print afternoon dress, a conservative black strapless, a heavy white shawl that she slings around like a matador's cape.

The concept was reminiscent of a Martha Graham psychological study, but I thought Bayón danced almost the same way in each of her memory incarnations. Her footwork usually doubled the rhythms of the musicians, and the amplification system was balanced so that you couldn't distinguish her sounds from theirs. She seemed to have a bottomless repertory of decorative arm movements, but I thought she got less interesting as the process unfolded.

Noche Flamenca's La plaza had all the unpredictable temperament that Bayón lacked, and none of her glamour — except for whatever it is that fascinates you and tempts you to dive off the rocks in a storm. Barrio herself is at the center of the whirlpool. She leads the players on at the beginning, a small sturdy figure in black pants, jacket, and a red shirt. You hardly notice her, but you realize there's an energy that's pulling the group together, rallying them to do their best in the series of numbers that follow. What's so fine is that all the performers are first-rate. (The singers were Manuel Gago and Emilio Florido, the dancers Sol La Argentinita and Rebeca Tomás, the guitarists Salva de María and Amir Haddad.) Antonio Jimûnez danced a solo of slashing gestures and spurts of fast footwork that accelerated to sudden defiant conclusions. Gago howled out a sad story whose words seemed all vowels, his clear tenor securely retaining the pitch even in the midst of sobs.

In the second half of the program Jimûnez and Barrio danced an alegrías that seemed less of a romantic duet than a dialogue across a force field that was drawing them together and pulling them apart. Finally, Barrio offered the last, long solo, an indescribable cascade of rhythms, impossibly fast but articulate heelwork hammering into the ground, a slow coda where she arched gradually into a deep backbend, and a final furious circle of reverse turns with her body arching back and one arm clutching her skirt in so we could see her feet.

After all that, with the audience on its feet cheering, the whole company joined in a celebration, visibly relaxed and blowing off steam with goofy afterthoughts. They finally strolled off singing, with a renewed sense of companionship after their struggle of public truthtelling.