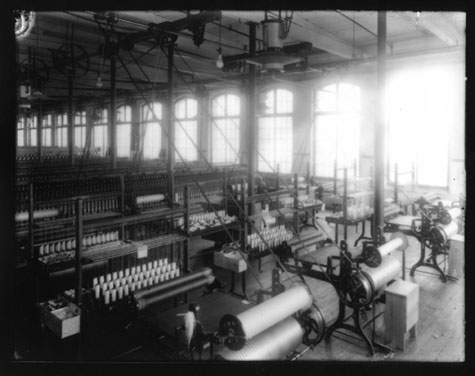

INFATUATION WITH INDUSTRY A textile mill. |

There is a golden formula in photography: photo plus time equals increasing allure. Old books and poetry, old television and movies can turn stilted, tedious. But photos seem to grow ever more compelling with age, even if the shots were boring when they were first made. It's something about the magnetism of the data frozen in the photographic moment — the clothes and architecture, the hair and cars. Even if you don't know the people or place in the photo, it draws you in. It's a glimpse into the past, a jolt of nostalgia, a tantalizing mystery.

This holds true in "A Fragile Memory," a magical — though at times frustrating — selection of 39 photos newly printed from an archive of 1000 glass plate negatives dating as far back as 1876 in the Providence Public Library's special collections. The photos, on view with some of the original negatives in the library's Special Collections Hall (150 Empire Street, third floor, through June 27), were printed at AS220's community darkrooms by exhibition organizer Agata Michalowska, darkroom manager Scott Lapham, and other members of the darkroom gang. The past documented here is somewhat familiar and yet strange, an exotic land a century away.

The standout shots are two 20x24-inch prints (all the photos here are contact prints, made without enlargement directly from the glass negative) of a giant steam engine on display in the glass and steel Victorian hall at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia to mark the United State's 100 birthday in 1876. It's a big elegant metal beast featuring a 30-foot-tall flywheel flanked by what look like massive pistons. It produced 1400 horsepower.

Providence engineer George Corliss developed this engine to be more efficient and run more smoothly than other industrial power sources, which made it favored by the textile industry. The machine, and the exhibition hall itself, herald America's arrival as an industrial power. The prints here are a feat of 19th-century invention, too, because of the rare large size of the negatives. You could see the images as an early inkling of Modernist art's — and in particular Modernist photography's — infatuation with industry. They may be the artistic grandfather of Margaret Bourke-White's iconic 1930s photos of factories.

But most of the images here are unidentified and unlabeled. They show the steel framing of a building under construction, waves crashing over Newport rocks, rows of machine looms in a textile factory, a wheeled cart with a sail, elaborate carvings on the side of an wood chest, five stacked boxes that turn out to be a foghorn, and a snowy farm in Seekonk. A happy man in vest and straw hat cradles a baby in his arms as a woman blurs in motion behind him. Women in long dresses cavort at a beach. A clapboard church in the classic Yankee style features a cemetery in front, and outside its fence a sign posted on a tree advertising a "Fair in Kingston." Another shot shows a street bustling with horse-drawn carriages and businesses, including a dentist, "fancy dry goods," an insurance office, and a shop selling books and toys.

Michalowska was introduced to the glass plate negative collection when volunteering at the library with special collections librarian Richard Ring. "There's a lot of mysteries involved," she tells me. Who took the photos, what they show, and how they ended up in the library's collection are — right now — unclear. (I suggest they post photos online and invite tips from the community.) So the images can feel unmoored in history — a particular frustration in photos like these that tend to be more interesting for what they show than how they show it.

Besides the Corliss photos, a couple shots stick with me. One is a pair of studio portraits of a weathered middle-aged woman. She appears severe, but in one shot betrays a hint of a smile. The negative is screwed up, but wrong in a right way, so that her head seems to emerge like a dream from a black mist. The other shows a large Victorian house that was (is?) around here somewhere. It stands alone, looming over an expanse of dirt road. At the street corner in the foreground, a pole supports wires — perhaps for a trolley line — a sign of the coming growth of the town, a sign of the future.

Read Greg's blog at gregcookland.com/journal.