1957: Charlie White re-creates American Graffiti — with black America walking out of the frame. |

“The Old, Weird America” | DeCordova Sculpture Park + Museum, 51 Sandy Pond Rd, Lincoln | Through September 7 “Matthew Day Jackson: The Immeasurable Distance” | MIT List Visual Art Center, 20 Ames St, Cambridge | Through July 12

VIEW: Photos of "The Old, Weird America" exhibit at DeCordova |

In the beginning, there was the Old West. The legend of the Old West's cowboys and Indians, flinty pioneers and buffalo killers, sheriffs and gunslingers started with the tall tales that cowboys themselves told of their glorious exploits. Then reporters did some more embellishing. And Buffalo Bill Cody, who had been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his fighting during our Indian Wars, started a circus in which he hired real Native Americans to re-enact with him the battles on stage. Which in turn inspired Hollywood Westerns.That sort of based-on-a-true-story version of our history, in which fact gets thrillingly mixed up with fiction and turns into national myth, is the focus of the DeCordova Sculpture Park + Museum exhibit "The Old, Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art," which was organized by Toby Kamps for Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

The title is borrowed from Greil Marcus's 1997 book about Bob Dylan's Basement Tapes, an album that came out of Dylan's noodling around with traditional and original songs in 1967 while he was holed up in upstate New York recovering from a motorcycle crash. In the songs, Marcus wrote, "certain bedrock strains of American cultural language were retrieved and reinvented" as Dylan channeled the rough-and-tumble outlaw America of old folk songs, murder ballads, tramp ditties, and blues.

"Old, Weird America" assembles 18 artists who mine this vein of American history/legend, who play at being old-timey. It's a ripe subject, and it maps what may be a generational trend — most of the artists here were born in the early '70s. Matthew Day Jackson's Garden of Earthly Delights (Spiritual America) is a wall of manufactured posters that he embellished with yarn, crystal-shaped line drawings, and collaged photos. It features images of Ronald Reagan bottle-feeding a chimp (from Bedtime for Bonzo), New Hampshire's Old Man of the Mountain, Disney characters, testimony from colonial Salem's witch trials, a 19th-century Albert Bierstadt American landscape, posters for the films Sasquatch and The Evil Dead, a jackalope, an astronaut, Bob Dylan, and Hieronymus Bosch's The Garden of Earthly Delights surmounted with a photo of Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics. It's a compendium of American heroes, monsters, paranoia, myths, and dreams that summarizes the show's subjects.

Margaret Kilgallen's floor-to-ceiling paintings and shanty towers immerse visitors in a cartoony derelict Main Street USA that offers a liquor store, a motel, a tire shop, a restaurant, and a jewelry store. A giant woman brandishes a broken bottle. It's warm, charismatic, handmade art that riffs on Mexican shop signs, tramp art, and carnival banners — art about the dirt and rust that reveal the lived-in, ramshackle heart of urban America.

Kara Walker's 2005 shadow-puppet video 8 Possible Beginnings: Or, the Creation of African-America: A Moving Picture by Kara E. Walker is a haunted fantasia chewing over the history of African-Americans. Sailors throw black captives overboard from a slave ship. An island, which rises up as a black giant, swallows the bodies. A black man picks cotton, then dances with a Colonel Sanders type. They wind up naked, with the white guy sucking the black man's cock and then stuffing cotton up the black man's ass. The black man grows pregnant and births a cotton sprite. The white guy lurks in pursuit of a little black girl. A little white boy forces Uncle Remus to tell him a story. Uncle Remus tells of Br'er Fox and Br'er Rabbit lynching black men from a tree.

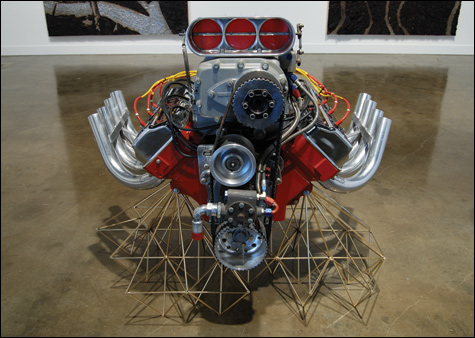

HEART OF PROMETHEUS: Matthew Day Jackson’s commission from “Big Daddy” Don Garlits typifies the vogue in middle-class guy taste. |

Walker's animations are a natural evolution of her terrific 19th-century-style paper-cut silhouette works. I prefer the paper stuff. Her static works are beautiful, brutal, suggestive, open-ended, alluringly mysterious tales of black and white in America, often shot through with a discomforting sexual charge. Her films make her points as explicit as bathroom graffiti, thereby closing off possibilities.

Charlie White's 2006 color photo 1957 re-creates the atmosphere of '50s white kids hanging around with cars à la George Lucas's 1973 film American Graffiti. A young black woman, in the background, walks out of the picture, her stance quoting the iconic photo of 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford being turned away from the segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. That fleeting glimpse suggests the blind spots required to believe these were all happy days.

Cynthia Norton's Dancing Squared features four red-and-white patchwork dresses hanging from the corners of a small metal carousel. When the carousel rotates, the dresses spin, and a disco ball on top glitters. It's like watching prototypes for robot Dolly Partons. It doesn't feel deep, but it's a hoot to watch.