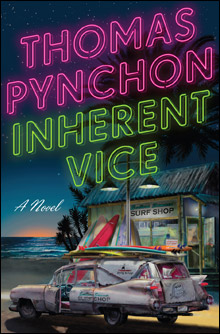

Inherent Vice | by Thomas Pynchon | The Penguin Press | 384 pages | $27.95 |

Paranoia isn't what it used to be — not for Thomas Pynchon, at any rate. Four decades after his shortest and in some ways best novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), he returns to the brain-fried '60s and its rarefied delusions of reference and crackpot conspiracy theories. But in lieu of the elusive, ineluctable Tristero of that earlier work, here the omnipotent secret society and sum of all our desires and fears is the Golden Fang. Never mind whether it's a Flying Dutchman–like ship or a conglomerate of dentists — for all its menace and profundity, it might as well be a Chinese restaurant.Neither does the hero of Inherent Vice boast the obsessive appeal of Oedipa Maas or any other Pynchon protagonist. A pot-smoking, acid-dropping, unregenerate hippie, Larry "Doc" Sportello makes for an unlikely gumshoe. (Or, as a character quips in one of the book's many lame attempts at humor, "gum-sandal.") Distinguished by his R. Crumb–like lechery and otherwise general inoffensiveness, he's Sam Spade by way of Cheech and Chong, prowling the streets of Gordita Beach (based, it seems, on Pynchon's own stomping grounds of Manhattan Beach), a funky surfing community outside LA. One day an old flame, Shasta, shows up in his office and asks him to investigate her current lover, Mickey Wolfmann, a billionaire real-estate mogul. Doc tries to pay the guy a visit but gets knocked out. When he wakes up, his LAPD nemesis, "Bigfoot" Bjornsen, has him marked for murder and kidnapping.

And so on. Usually it's that "and so on" that is Pynchon's genius, the gleeful labyrinth of narrative, symbol, slapstick, and arcana that lures you in, goes nowhere, and never really lets you out again. Now it just goes nowhere. Doc's trail consists of dead ends, mischance, and treachery, a hodge-podge of Chinatown, The Long Goodbye, and other noirs, but it seems he'd much rather be back home with a bong, a burrito, and reruns of Adam-12. That last being one of the ceaseless pop-cultural references dropped in every page, many of them made up.

In better days, of course, the made-up ones were as funny as the real ones. Here we have a Beach Boys–knockoff surf band called the Boards, who also might be zombies, and who figure somehow or other in the tiresome plot. Their ditties pale before Pynchon's previous songwriting efforts. As for the expected loony, cryptic character names, "Coy Harlingen" proves all too apt in describing the book's overbearing tone.

So it's a long way around the block for little reward. And though it's true that Pynchon never pays off in terms of closure or neatly resolved meaning (that being the point), in InherentVice, ambiguity deteriorates into inanity. He's either trying too hard or not hard enough. Okay, you could scarcely expect another densely woven, absurdist masterpiece so soon after 2006's magnum opus, Against the Day, which at nearly 1100 pages weighed in as Pynchon's heaviest tome to date. Then again, Lot 49 came out only three years after his groundbreaking debut, V.

It seems, in short, almost an act of desperation. Rumor has it that Pynchon's agents are looking to get a movie deal for this book. Which would be a first for him. Could this be Inherent Vice's own inherent vice — that it was written for a paycheck? Occasional glimpses of Pynchon the postmodernist titan do peek through the palaver, like this tossed-away snatch at the very start: "Does it ever end, he wondered. Of course it does. It did." Let's hope the words aren't a self-fulfilling prophecy.