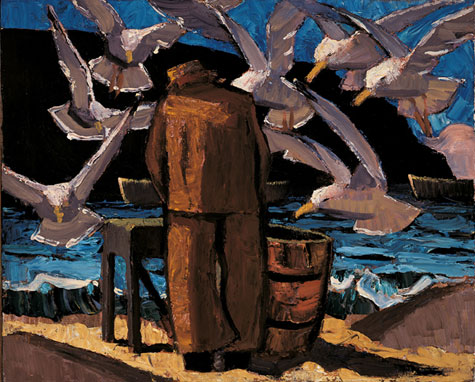

"MATINICUS" Oil on canvas by George Bellows, 32 x 40 inches, 1916.

|

Long ago an art critic of my acquaintance remarked that New York was a border town to Europe, and until fairly recently that was true. Artistic ideas would be born in Europe, often France, and migrate slowly across the Atlantic and take root.

Thus it was with painting outdoors. The Barbizon painters — Millet, Corot, and the others — steeped in the revolutionary ideas of 1848 and easy travel by the new railroads, settled in Barbizon, took their easels outside, and changed painting. The Impressionists followed, changing painting even more and finding new places to go. American painters, training in Europe, transplanted these ideas stateside and started traveling and gathering in groups, changing American art for good.

The American Impressionists, when they left the city, tended to settle along the coast of Connecticut, in Cos Cob and Old Lyme. Charles Woodbury came up to Maine and set up a studio and a summer school in Ogunquit. Artists had been going to Monhegan for many years, but Robert Henri brought people like George Bellows and Rockwell Kent, and another colony was born. They built summer places, rented studios, taught, partied, did some local shows, and enjoyed summers away from the city.

The presence of all these artists in summer residence has left a legacy of art being made and shown here and, eventually, of museums (another legacy of 19th-century Europe). Two of these, the Portland Museum of Art and the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut, have produced "The Call of the Coast: Art Colonies of New England," a show that documents how work done in New England summers affected American art.

Some of the artists who went to Connecticut have a firm place in art history, while others are not known so well. Most notable is Childe Hassam, represented here by a striking picture of slender saplings set against rocks, "The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut." Hassam pulls coherence out of disparate colors and tones laid in quick strokes, a technique he learned in France, and had the ability to do well.

One also sees noted Americans like Willard Metcalf and John Twatchtman, and some lesser-known artists like Edward F. Rook and Clark Vorhees. Taken together they build up a coherent picture of the Impressionism-based artistic thinking of the day.

Ogunquit, while active at the same time and a little later, turned into a hotbed of early modernist thinking — a step past Impressionism and toward more abstracted concepts. Walt Kuhn was breaking the picture up into heavy strokes, Bernard Karfiol and Yasuo Kuniyoshi were developing a new way of modeling the figure, and Abraham Walkowitz was breaking the picture into local color areas. Here again, they were starting from work they had seen of Picasso, Matisse, and others, and cross-pollinating it with their summers by the sea. The show gives a clear sense of the threads that bound them together.

When Robert Henri got to Monhegan in 1903, he decided that his friends and students should come there as well, and he dragged Rockwell Kent and Edward Hopper to the island. Kent really took to it, and built a place for himself. Pretty soon George Bellows and Randall Davey showed up, and then more and more arrived, as they still do. While never a real "colony," the artistic community has thrived for years, bringing such worthy artists as Abraham Bogdanove, Eric Hudson, Andrew Winter, James Fitzgerald, Reuben Tam, and many others.

This show is a fine backward look, and a chance to sample what some really interesting people were thinking about while they were enjoying what those of us who live here love about being here. Because of them, art runs deep here in Maine, and that has a lot to do with what makes it special.

Ken Greenleaf can be reached at ken.greenleaf@gmail.com.

THE CALL OF THE COAST: ART COLONIES OF NEW ENGLAND | through October 12 | at the Portland Museum of Art, 7 Congress Square, Portland | 207.775.6148 | portlandmuseum.org