For decades, feminists have rallied behind the phrase “the personal is political,” meant to remind us that our personal lives (including our reproductive choices) are intrinsically affected by politics. Yet even while they remind society that public acts can penetrate private spheres, many members of the pro-choice movement still shy away from telling personal abortion stories, finding it more comfortable to talk about reproductive rights as intangible concepts rather than concrete situations.This keeps the pro-choice cause stagnant, and struggling to be relevant to a wider audience. It also hurts women who have had abortions. Jennifer Baumgardner’s new book, Abortion and Life (Akashic Books) is one step toward shifting that paradigm, first by acknowledging that many people (feminists included) are still “afraid to discuss abortion in polite company,” and then by underscoring the importance of storytelling.

Part of the lingering stigma attached to abortion is based on anti-choice rhetoric and scare tactics. But just as insidious is the pro-choice movement’s reluctance to delve into the emotional nuance that comes with terminating an unplanned pregnancy. For example, it’s largely unacceptable for a pro-choice woman to be ambivalent about her own abortion (she would seem too vulnerable). Nor is it considered appropriate for a woman to express an excess of relief, or an outright absence of emotion, about the event (too callous). It’s as though women’s experiences of abortion have been passed through a filter for years, with only “on-message” stories allowed to reach the public. The results: a society that still considers abortion a clandestine act; a diverse group of women who feel both isolated and lumped together; and a movement that feels quite impersonal and manufactured, focused single-mindedly on a concept rather than a reality.

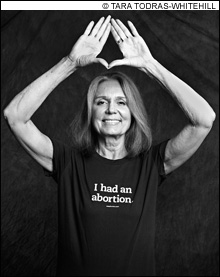

Enter Baumgardner’s “pro-voice” strategy, which started taking shape in 2004. That year, as a throwback to second-wave feminist efforts in the 1970s “to put a face on this diverse issue,” she made the first batch of T-shirts that read: “I had an abortion.” The T-shirts, distributed first at an abortion-rights march in Washington DC and then nationwide through Planned Parenthood, were wildly popular (and controversial) — more than she’d ever expected them to be — and indicated an untapped desire among women to destigmatize the abortion experience.

GLORIA STEINEM: The pioneering feminist is

one of many who tells her story in the book. |

Meanwhile, Baumgardner had begun work on the documentary Speak Out: I Had An Abortion, released by SpeakOut Films in 2005. In collecting money and stories for that documentary, she found scores of women aching for an outlet to speak about their abortions in an honest way — to become stories instead of stereotypes. And in letting them do so, she outlined a new direction for the pro-choice movement.“In encouraging women to tell their stories, we hope to demonstrate that women might have complex, or even painful, experiences with abortion, but they are still grateful to have had access to the procedure — very, very grateful,” she wrote in her mission letter for the film.

This month, Akashic Books released Abortion and Life, in which Baumgardner and photographer Tara Todras-Whitehill translate the ideas (and some of the narratives) from I Had An Abortion into print. The book presents a trim history of abortion in the United States (skippable if you’re familiar with the hot-button milestones), followed by Baumgardner’s theoretical arguments, and then 15 women’s first-person abortion stories. Each narrative is accompanied by a photograph of that woman wearing the black “I had an abortion” T-shirt.

A’yen Tran, a 20-something woman, talks about the physical and emotional differences between her first abortion (physically unbearable, emotionally difficult) and her second (relatively painless, emotionally supported).

Barbara Ehrenreich, the author and activist, says: “My abortions were not morally or emotionally wrenching for me. I was just relieved each time I had the procedure.”

Gillian Aldrich, who co-produced the documentary with Baumgardner, and whose mother shares her own story in the book, recalls making the decision: “I thought: If there is a baby in here, it’s not staying... Neither of us was mature enough. We weren’t young, but we had a lot of growing up to do.”

Amy Richards (Baumgardner’s co-author on two previous feminist books), tells of her selective reduction, in which two of the triplets in her womb were aborted (the third would continue to term).

“Why are these stories so important?” Baumgardner asks. “Because a story is not a debate, it doesn’t have sides. Unlike an argument or a slogan, a story can be as complex as a woman’s life. Listening to women’s abortion stories today serves a dual purpose: It reflects the urgency of abortion rights, and if we are listening and if we are creative, it indicates places where the movement needs to go.”