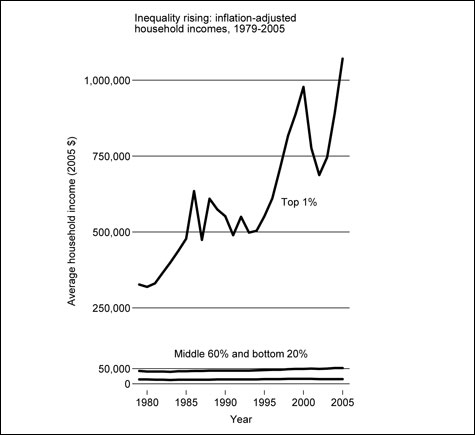

VAST GAP Comparing income growth for the bottom 20 percent of Americans, the middle 60 percent, and the top 1 percent. CREDIT Lane Kenworthy, University of Arizona, Congressional Budget Office data. |

It seems as if there’s no light at the end of the state’s gloomy fiscal tunnel.

The recession has caused tax revenues to plummet. The cost of government has been higher than expected. Our governor and legislators, Democrat or Republican, uniformly feel they must respond by radically cutting the state budget. They’ve already cut — and are sharpening the knives to cut deeper — funds for public schools, community colleges, university campuses, and services for the old, poor, sick, mentally ill, developmentally disabled, and prisoners. And many services have been serially slashed for years.

Just last April, the Legislature sliced away $118 million from the state’s current two-year budget. Then in November Governor John Baldacci cut another $80 million. He’s asking the new Legislature to approve that move, and on December 16 he announced he wants to cut another $15 million, besides taking $45 million out of the state’s reserves.

And officials project a colossal $840-million shortfall in what had been a $6.8-billon General Fund budget for the next pair of fiscal years (called the biennium), beginning July 1. Since human services and education make up 80 percent of the budget, they will continue to be the big targets. For the same period, a $556-million hole has appeared in the $1.2-billion state highway fund, which is financed largely by a tax on gasoline.

Curse the recession, which may become the biggest economic downturn since the Great Depression. But there is a huge irony in the response of Maine politicians to the recession — an irony first appreciated in the 1930s: Putting aside the waste of not educating young people as well as they could be, putting aside the unfairness and cruelty of not caring properly for the most vulnerable in society, most economists agree that cuts in the state budget make the recession worse.

Cuts mean layoffs for state workers and local teachers (school budgets depend on state aid), as well as for people at nonprofits that receive state money to care for the needy, and at firms dependent on government contracts. The “ripple” effect hits stores and other businesses indirectly reliant on government spending. With more people out of work and spending less, income- and sales-tax revenues will decline, but more people will need state services. It’s an economic whirlpool.

Economists agree that in a recession the government should increase spending to stimulate economic demand, to get the economy moving again. “Economics is really clear on this point,” says University of Maine at Farmington economist John Messier.

In the 1930s, when Democratic President Franklin Roosevelt fought the Depression with massive federal-government spending, putting into practice the new theory of British economist John Maynard Keynes, Roosevelt was partially thwarted by state and municipal budget-cutting. The same cross-purposes are now being set up.

President-elect Barack Obama, another Democrat, is preparing to spend as much as $850 billion in an economic stimulus to make over America’s infrastructure — to repair highways, bridges, and schools, and institute society-wide energy conservation and the development of alternative energy sources.

Thus, Maine governmental budget slashing is “the exact wrong thing at the wrong time,” Messier says.

Economist Charles Colgan, of the University of Southern Maine, told Mainebiz: “Even while the federal government is stepping on the accelerator, the states and local governments are stepping on the brake.”

But Maine’s constitution requires a balanced budget. Unlike the federal government, the state can’t indulge in deficit spending; it can’t borrow to cover current expenses. So do we have no alternative but to cut services, maybe pinning some hope on the local effects of Obama’s stimulus package?

Although state departments are giving the governor wish lists of how federal stimulus money could be spent (much will be channeled through the states), at his December 16 news conference Baldacci said Obama’s aid “won’t be able to help in the initial budget” for the next biennium. And even if Maine gets federal infrastructure money this year, it may not help with education and human services.

Yet there are alternatives to state-budget cuts. They are available right now or in the immediate future. Here are four possible state actions developed with the help of a couple of Maine economists and backed up by the advice of national experts. These actions will help us get out of recession.

Alternative 1: an income-tax “recession surcharge” on the wealthy

Clearly, if state taxes were raised, fewer services would need to be cut. But increasing taxes gives people less money to spend, and that would tend to push the state further into recession. Some economists, however, say we can get around this dilemma by increasing taxes only on the people who have extra cash.

“In the short run, take from the people who can afford it to protect the people who obviously need help,” says Messier.