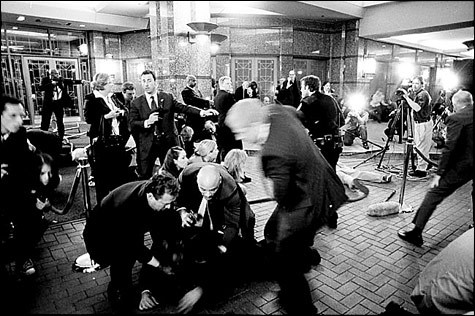

NOT SEEN ON TV: Were anti-hate-speech strictures to tighten, there would be less leeway for political protest or satire — namely, films like the British mockumentary Death of a President (above).

|

Anthony Lewis's free-speech credentials are impeccable: among other things, the former New York Times columnist is James Madison Visiting Professor of First Amendment Issues at Columbia University's journalism school; was fêted by the National Coalition Against Censorship this past fall; and chronicles the First Amendment's history in his most recent book, Freedom for the Thought That We Hate: A Biography of the First Amendment (Basic Books).Recently, though, Lewis has been reassessing the legal standard for how far threatening speech should be allowed to go. The key precedent here is 1969's Brandenburg v. Ohio, in which the Supreme Court ruled that calls for violence against Jews and blacks at a Ku Klux Klan rally were legal: such advocacy is protected, the court found, unless it's "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action."

Harvey Silverglate — the chairman of the board of directors of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, and a regular Phoenix contributor — explains the "imminence standard" thusly: "If you get a speaker who gets up there and says, 'All Jews and blacks should be hung,' that is fully protected. But if the speaker says, 'There's a Jewish neighborhood or a black neighborhood two blocks down the road. Let's go down there and lynch them,' that gets into an area where the speech that's recommending action becomes more realistic — more imminent."

In Freedom for the Thought That We Hate, however, Lewis suggests that, in the context of the so-called War on Terror, a more expansive reading of Brandenburg's imminence standard might be appropriate. And he makes a similar — albeit hypothetical — argument regarding anti-Obama speech.

"If somebody tried to assassinate Obama," says Lewis, "and upon further examination it turned out that they were a regular listener to Sean Hannity [of Premier Radio, ABC Radio, and Fox News] — and decided, on the basis of Hannity's many broadcasts, that Obama was trying to destroy the United States — would that justify shutting Hannity down and curbing speech in some way? It's hard to say . . . but if it had that effect, surely the imminence requirement is at least partially met."

Surprisingly, Lewis isn't the only civil libertarian thinking along these lines. Gene Policinski, the vice-president and executive director of the Tennessee-based First Amendment Center, says there's a chance that the courts will pay closer attention to extreme anti-Obama speech than they have to speech regarding previous presidents. "I think there's great concern, since he's the first African-American president," says Policinski. "And given our history of violence directed at African-Americans — particularly those who stand out by challenging the status quo — the courts may see these kinds of expression in a much more serious and immediate way." (One of those African-Americans, Martin Luther King, was assassinated in the state where the First Amendment Center is headquartered.)

But altering free-speech protections out of concern for Obama could have devastating implications for our collective right to criticize political authority. Think back to 2004: even though the nation was engaged in multiple wars and guarding against another 9/11 — and even though President George W. Bush was genuinely despised by a healthy segment of the populace — author Nicholson Baker was still free to write and publish Checkpoint, a novel in which two men debate taking Bush's life. And two years later, the British mockumentary Death of a President— in which Bush's (simulated) assassination is followed by a third Patriot Act and a massive crackdown on civil liberties — was allowed to open in the United States, despite public condemnation and the unwillingness of some theater chains to screen it.

The ancillary effects of such a hypothetical expansion also need to be considered. New restrictions on anti-Obama speech could legitimize paranoid conservative fears that Obama plans to silence his opponents, for example — thereby exacerbating anti-Obama animus. Consider, too, that by making hateful attitudes known, the First Amendment allows society to respond in kind. "The theory of the First Amendment actually makes a lot of social sense," notes Silverglate. "It's very useful to know who wants to hang the Jews and the blacks." Penalize the ugliest anti-Obama speech, and this benefit vanishes.

If you're an Obama booster who thinks concern for his safety might justify even an incremental erosion of free speech, ask yourself: did Checkpoint and Death of a President bother you at the time? Do they bother you now? (Be honest.) And how would you feel if — four or eight years from now — expanded limits on speech that originated during an Obama administration led to the censorship of texts deemed too threatening to, say, President Sarah Palin?

"We need to have historical humility," says Nadine Strossen, the former president of the American Civil Liberties Union and a professor at New York Law School. "Each era tends to have historical hubris — 'This is the greatest danger ever posed to the values we hold most dear.' We tend always to exaggerate the danger — and to unnecessarily cut off civil liberties."