On a tour of the studios at 337 Summer Street, Jen Mecca, a textile artist, points out some of the spaces recently vacated by artists and craftsmen, including a pair of furniture makers who left for Somerville. In one studio, a poem is daubed on an iron beam, in another designs are sketched on sheet-rock walls. "It's weird how quiet it is in here now," she says.

She's hoping to get someone with a camera in to document the space. It's only a matter of time before the building will be cleaned out and sealed off.

Mecca and the other artists who rent space in this five-story brick walk-up are remnants of what was once Boston's largest and most prominent artist community: Fort Point, a cluster of brick warehouse buildings across from Boston's Financial District. For the past year, they and other painters, dancers, filmmakers, designers, musicians, and craftsmen at two other nearby buildings — nearly 80 of them all together — haven't known if they would be able to stay in their studios, or if they would join the waves of artists who have been displaced from the neighborhood in recent years.

While Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) officials insist that they've come up with a plan to keep the artists around, the agency has now opened the gates for a series of projects that would allow the conversion of former artist-occupied buildings into offices, and potentially for the construction of the highest residential tower the neighborhood has seen. For many artists, especially those who pioneered Fort Point and helped it become one of Boston's most coveted frontiers for development, the plan amounts to a shell game, as the city shifts them around while allowing the neighborhood to turn into an annex of Downtown Boston.

Through it all, the artists have looked to City Hall for help. Why, one may ask. After all, powerful developers muscling out poor artists — the very people who made a once-forbidding neighborhood hip and desirable — is nothing new. The answer is because the BRA and the mayor have long claimed that the city is committed to its artists, and those in Fort Point in particular. Boston is one of the only cities in the country with a full-time program, the Artist Space Initiative, dedicated to preserving and building artist housing and studios. And the BRA has commissioned exhaustive studies on the importance of promoting the city's creative economy, such as a 2006 report, "CreateBoston," which stressed that the arts-related industries "highlight neighborhood history and traditions, serve as anchors for downtown and neighborhood revitalization efforts, and promote tolerance and diversity."

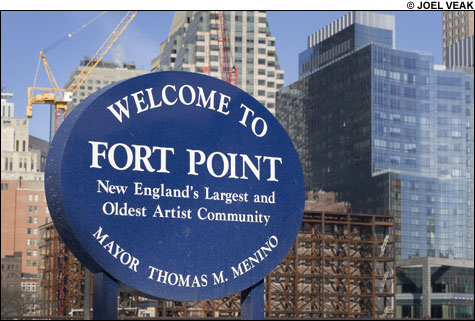

Indeed, on the official sign situated on the Summer Street bridge for pedestrians crossing from the Financial District, the city proudly proclaims Fort Point to be "New England's Largest and Oldest Artist Community," and, by virtue of the fact that Mayor Thomas Menino has adorned his name to the sign, as well, seems to have given protecting artists in the neighborhood his personal imprimatur.

"No one is a bigger supporter of artists than Mayor Menino," insists Dot Joyce, his spokeswoman.

But they're not feeling the love in Fort Point these days. Despite the BRA's relocation plan, dozens of artists are planning to leave the neighborhood. Since the mid 1990s, Fort Point's artist population has dwindled from around 600 to now barely 200.

In other words, these days, the claim on the official Fort Point sign seems dubious, as artists have left in droves for more hospitable and affordable communities, such as Providence and Lowell, where at least 600 artists are now estimated to live. The sign does, however, serve one useful function: so many storefront galleries and arts-related business have closed in recent years — Studio Soto, Mobius, the Revolving Museum — thus so significantly changing the landscape and vibe of "New England's Largest and Oldest Artist Community," that someone stumbling into Fort Point might never otherwise know artists even still live and work there.

THE SIGN’S FINE: But despite Mayor Menino’s pledges of support, many artists in Boston’s Fort Point neighborhood are feeling less than welcome these days. |

Indulged and ignored

Starting in the 1970s, artists began settling on the vacant floors of the old textile warehouses of Fort Point, many of them owned since the 1800s by the Boston Wharf Company. The city came to embrace the artists, even tweaking the zoning code to allow them to live and work in areas that, like Fort Point, were zoned for manufacturing.

Former mayor Ray Flynn, Menino's predecessor, recalls that his administration helped bring the Children's Museum into the neighborhood. Reflecting on the current tensions, Flynn, a South Boston native who worked on the docks near Fort Point back in the day, says, "I believe nobody has a better interest in a community than the people who live there and who are invested there. When it comes to making decisions about neighborhood use, it has to be a round table."