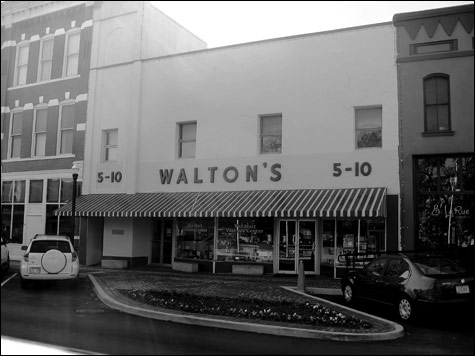

IT STARTED HERE: Walton framed the big-retail ethic in terms of “family” while removing the taint of servitude from service labor. |

| To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise | By Bethany Moreton | Harvard University Press | 384 pageS | $27.95 |

Many Americans feel as if they'd been living helplessly amid the handiwork of extraterrestrials, as if a spaceship had suddenly blown in and zapped the landscape with suburban sprawl while sucking up middle-class wages in exchange for low-paid service work. What's even weirder is that those most hurt by this alien dispensation have been the most likely to embrace it. How did this happen?The reason for our bewilderment, explains historian Bethany Moreton in To Serve God and Wal-Mart, is that we're stuck in an old narrative about the American worker that's based on the experience of the industrial Northeast and Midwest. In that story, farmers across the Western world went into American factory work for a few generations, formed unions, then found themselves with low-paying service jobs as industry began outsourcing to the South and overseas.

True enough, but what's missing here, Moreton argues, is an account of the sing-hallelujah service culture that had been incubating in the agricultural communities of the Ozarks, where Wal-Mart is headquartered, since the '60s. Here, farm kids never entered unionized factory work but went directly into the retail-service sector that formed the backbone of the rising Sun Belt economy. At the epicenter of that world, shaping its business model and cultivating its "corporate populist" sensibility every step of the way, stood Sam Walton. When the Berlin Wall came down and international markets opened up in the '90s, he had an army of well-trained, deeply networked Christians eager to expand Wal-Mart's service culture and gospel of free enterprise, first in Mexico, then . . . well, you know the rest.

It was "Daddy" Walton's genius to frame the big-retail ethic in terms of "family" while removing the taint of servitude from what was, after all, unproductive service labor. He had a lot to work with. The predominantly white, small-family farming region of the Ozarks had an "unusually flat class structure," and that blurred the line between its female customers and its clerks. Walton made the cheerful, down-home, everyone-pulling-together family-farm values of his early frontline retail workers a hallmark of his emerging behemoth while earning their loyalty through policies, like flexible scheduling, that respected their "home duties."

Meanwhile, Wal-Mart preserved male authority in its management structure — and drove the poor sons of bitches hard — but with a twist. As the company gained traction in the mid '70s, the conservative Christian movement taking shape throughout the heartland shifted toward an ethic of "servant leadership" that not only rendered masculinity compatible with service work but sacralized fatherhood and reinvested men in the domestic sphere during a time of rising divorce rates. The reproductive politics so puzzling to liberals is grounded in the theology of the "servant heart" to which both men and women in Wal-Mart World aspire — at home, at church, and at work.

Although Moreton's argument about gender is central and accounts brilliantly (if at times at a stretch) for the political phenomenon of the Sarah Palin–lovin' Wal-Mart Mom, her book is primarily an economic and business history. Walton was an extraordinary innovator who not only worked sympathetically with the culture at hand but led the way in computer technology, logistics, and the integration of "academic" resources with industry's vocational needs. To understand the lingua franca of today's workplace — with its talk of networking, entrepreneurialism, leadership, community service, and, above all, PR and communications — this book is indispensable reading. After all, we all live in Wal-Mart World now.