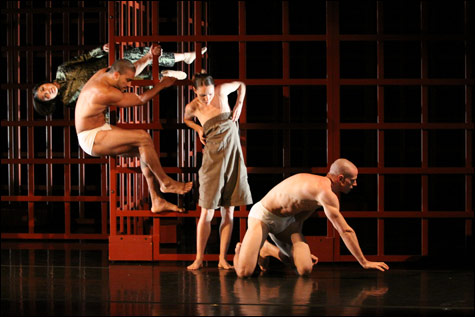

ORBO NOVO: In Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s world premiere for Cedar Lake, the dancers tumble, twist, roll, shudder, struggle, and collapse, answering a primal instinct to keep going. |

Postmodern dance's conceptual, physical, and metaphysical roots spread far and wide, as four summer festival performances attested last week. The three newly minted works and a 30-year-old classic all used invented movement vocabularies with a tip of the hat to the formalities of ballet, they all applied highly theatrical staging effects, and none of them looked the least bit like the others.

At Jacob's Pillow, life was giving a hard time to the dancers of Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet and Andrea Miller's Gallim Dance, and they were making the most of it. Cedar Lake's Orbo Novo, by the Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, meditates on the idea of disability, inspired by the author Jill Bolte Taylor's account of experiencing a stroke. Sections of this harrowing text are recited in perfect vocal and gestural unison by Jubal Battisti and Kristen Weiser. They're joined by the other 16 dancers, speaking or mouthing the words in choral formations.

This preamble prepares us for the dance's metaphor of resistance. A massive wall of sliding lattice-work panels (by Alexander Dodge) cages and releases the dancers, separates them, and finally herds them together in a desperate, struggling cluster. Some of them are able to wriggle through its openings, and the whole structure can be pushed apart to allow for intervals of dancing.

Cherkaoui has invented a movement vocabulary that draws on the shifting, fluid center of weight employed in contact improvisation and the articulated, topsy-turvy acrobatics of hip-hop. From the premise that any part of the body can be totally flexible or inoperable at any given moment, the dancers, in groups and solos, tumble, twist, roll, shudder, struggle, collapse, answering a primal instinct to keep going.

The men of the company had most of this infinitely mobile movement to do, but Ebony Williams (a product of Boston Ballet School and Boston Conservatory) had a remarkable solo in which she'd unlock a limb and send it vigorously out into space, only to lose control of it and start unlocking another body part. The impressive, post-minimalist score by Szymon Brzóska was played live by the Mosaic String Quartet with guest pianist Aaron Wunsch.

You can't really track where Andrea Miller's movement comes from. The six dancers in Blush, which she choreographed for her company, seem to exist in a state of constant rage that's either being suppressed or being vented on some colleague. To begin the piece, a man poses and crouches, spars and sprints around the space. He could be a boxer, a muscle man, some athletic character, or someone else altogether. The images flash by before you can really know him.

Three women appear, dancing in unison, evolving slowly into poses and bursting out of them only to ooze into new ones. The three men are lying on the floor upstage in a ghastly silver light (by Vincent Vigilante). The women imply but don't exactly copy the seductive poses of fashion models. Shoulders a-tilt, elbows lifted, they frame their faces and draw attention to their upper bodies. They suddenly turn into harpies, stooped over and clawing in the direction of the men.

For an hour the dance tosses you between half-realized but powerful spasms of desire and pursuit, seduction and mockery, attack, suffocation, and passivity, in no particular order and with no particulars about cause and effect. Sometimes there's weird, Japanese-sounding pop music — manic rock with what could be loud bleats from an ambulance mixed in, a mournful child-woman's voice singing about rainbows and sunshine. Sometimes there's Chopin.

Powdery smudges appeared on the floor, possibly a butoh-like white make-up that had rubbed off the dancers. I noticed alarming red blotches on the dancers' skin, maybe from the rough contact they were having with each other and the floor, and I watched to see whether the blotches would subside.

BLUSH: The dancers in Andrea Miller’s new piece seem to exist in a state of constant rage. |

Two men kept snatching a woman and holding her in vertiginous lifts. A woman launched provocative moves at a cowering man. People dragged limp partners across the floor. Women stood facing away from the audience and snapped into perfect fifth position, then tipped forward, drawing your eyes to buttocks rimmed with tiny black tights. Two men played endless awkward games, wrangled in one-sided embraces, ran while clamping their heads together. There seemed to be no rest or release for any of it.Dance without end, dance for its own sake, but relieved of sexual tension, was one foundation stone of postmodern dance. At Bard College, Lucinda Childs revived Dance, her 1979 collaboration with Philip Glass and filmmaker and painter Sol LeWitt. By the end of the '70s, Childs, the most pristine of the postmoderns, was adding theatrical elements — lighting, projections — to her stepping-pivoting-leaping dances. Dance was a visual spectacle without dramatic implications. It was stunning to see it again in a time when you can hardly encounter two minutes of dancing that isn't wanting to rip your heart out.