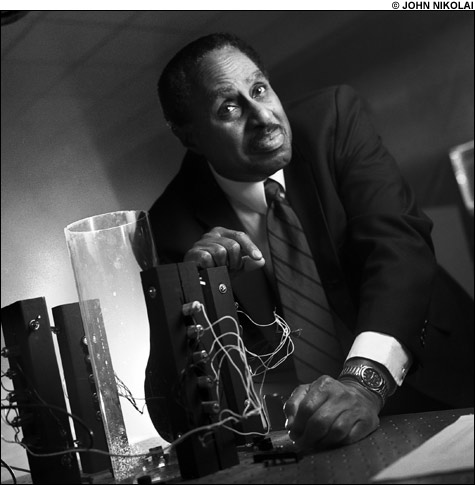

PERSONAL QUEST Since losing his father 53 years ago, Mallett has devoted his life to building a time machine in order to revisit him. Today, in a Connecticut laboratory, he’s developed basic equations and a prototypical experiment that may prove it’s possible. |

Dr. Ronald L. Mallett was only the 79th African-American to earn a doctorate in physics. But being black wasn’t the only potentially complicating factor he faced on the road to becoming a tenured theoretical physicist at the University of Connecticut.

Another was his reason for choosing his vocation, one he kept hidden for years, fearful that its discovery would (at best) incite howls of derision from his colleagues, or (at worst) amount to professional suicide.

Ronald Mallett wanted to build a time machine.

Traveling into the future is easy. Anyone familiar with Albert Einstein’s special theory of relativity knows a moving clock ticks slower than a stationary one. So it’s simple, really: all you have to do is build a spaceship that moves nearly as fast as the speed of light, pump it with enough fuel for a long — long, long — round-trip voyage, and head for the stars. By the time you return to Earth in, say, five years (as marked by you onboard your light-year-traveling spaceship, of course), you’ll have aged half a decade while everyone and everything else on Earth has aged considerably more.

But who wants to go to the future? (Nowadays, it’s terrifying even to ponder what the headlines will be tomorrow.)

Certainly not Mallett. For more than 50 years, he’s been obsessed with finding a way to return to the past. Specifically, to the Bronx, in 1955. That’s the year his father, Boyd Mallet, died. Mallett’s lifelong mission? To traverse spatiotemporal continuum and warn his dad to take better care of himself. To tell him to kick the two-pack-a-day habit that helped lead to the fatal heart attack he suffered at the age of 33.

The “overwhelming shock” of his father’s death caused Mallett, now 63, to “just disconnect from reality,” he says. So when, at age 10, he started building a jury-rigged jalopy, based on the gyroscopic contraption on the cover of the Classics Illustrated version of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, it might have seemed as if he had gone over the edge.

But the next decades only saw Mallett’s focus on his mission intensify with laser-like precision. He devoured every book on Einstein he could find. He boned up on differential equations and tensor calculus. And by 1973, at Penn State, he’d earned his Ph.D. Moved by the intensely personal nature of his quest, Spike Lee announced this past summer that he’s currently writing a screenplay for a movie — which he’ll direct — based on Mallett’s book, Time Traveler (Thunder’s Mouth, 2006).

On Mallett’s cluttered desk sits a small placard: “If the facts do not conform to the theory, they must be disposed of.” A bit of geek humor. But Mallett knew that there was nothing in the laws of physics that said time travel was impossible. And now his groundbreaking theories about the nature of space-time are about to be borne out in a Connecticut laboratory.

Many scientists have wondered about the possibility of time travel, says Dr. Philip D. Mannheim, a UConn professor specializing in particle and field theory who occupies the office next to Mallett’s, but it’s always “only ever been at the theoretical stage. Ron is one of the people who is actually setting out to do it. The proof of the pudding will be in the eating. The theoretical ideas that we have seem to permit it. But nonetheless, you still want to see it happen. And that’s what Ron is doing. He’s worked through [Einstein’s theory of] general relativity to find a way to apply these ideas in a tractable situation.”

Mallett is convinced that time travel will become a reality sooner rather than later. “What I’m doing, I like to think of as analogous to the Wright brothers,” he says. “They sent this rickety craft across a few hundred yards of beach. But with the technological acceleration that happened after that, by the middle of the century we had intercontinental air travel. This is only the beginning. Once it can be shown to be done, even in the simplest case, then what we learn from that will be incredible.”

The death of Superman

When I first meet Mallett, he’s just returned from the premiere of Miracle at St. Anna in New York. He’d attended as one of Spike Lee’s invited guests, and he shows me a stack of snapshots of him posing with Lee, and with the film’s cast.

The film had tremendous sentimental value for him. “My father was in the Second World War,” notes Mallett. “He was with the troops that went across the Rhine. It was great for me that this movie emphasized the role of African-Americans in the war.”