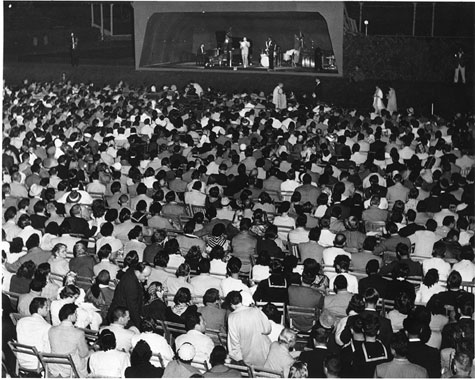

WEIN'S BACK PAGES The crowd at the first Jazz Festival in 1954;

|

Forty years after a half-million hippies descended on a sprawling dairy farm in upstate New York, Woodstock has become shorthand for an entire epoch.

But it is hardly the only music festival to serve as mythmaker. As cultural touchstone.

At the Monterey Pop Festival in the summer of 1967, Jimi Hendrix torched his guitar in a gesture that would jumpstart his stateside career and signal the start of the Summer of Love.

A quarter-century later, Perry Farrell of Jane's Addiction pushed a new counterculture into the mainstream with his Lollapalooza festival.

And in the late '90s, singer-songwriter Sarah McLachlan struck a blow at the male-dominated music machinery with her all-women's tour, Lilith Fair.

The summer festival has made cultural history for decades now, drawing on a mix of sunshine and showmanship, media savvy and marketing muscle, chutzpah, and hustle.

It is a complex alchemy. A sort of magic, when it works. But if it is difficult to define, its origins are clear.

Before Monterey and Woodstock, before Lollapalooza and the Warped Tour and Bonnaroo, there were the Newport folk and jazz festivals.

And the Newport gatherings — celebrating their fiftieth and fifty-fifth anniversaries with shows last weekend and this — are, at bottom, the work of one figure: George Wein, a minor jazz pianist from suburban Boston who is the undisputed father of the American music festival.

THE IMPRESARIO 'I have a slogan,' Wein says. 'Commercialism with credibility.'

|

LEAVING STORYVILLEWein (pronounced Ween) grew up in Newton, Massachusetts — a Jewish kid listening to Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. And by 13, he was playing in a band in his cellar.

"I had three trumpets, two trombones, four saxophones, and a rhythm section," he said.

After graduating from high school, Wein served in the Army for three years and attended Boston University, playing piano in jazz clubs as many as seven days a week for five and six weeks at a time.

Nat Hentoff, who was working at a Boston radio station at the time and would go on to become a columnist for the Village Voice and a staff writer for the New Yorker, recalls a particularly skillful rendering of "Oh Look-A-There, Ain't She Pretty" at the Savoy Café on Massachusetts Avenue.

"George," he said, "was a very good pianist."

Wein met his future wife Joyce Alexander, jazz columnist for the Simmons College newspaper, backstage at a Sidney Bechet show during his junior year — though it would be a number of years before the interracial couple wed.

"It was the taboo, the invisible line that we would be crossing," Wein wrote, in his autobiography Myself Among Others, recalling his parents' early objections to marriage. "It would be a shanda for the neighbors."

But if Wein's romantic ambitions stalled, his musical ambitions did not. Just out of college in 1950, he secured space at the Copley Square Hotel and opened Storyville, a club named after the old New Orleans' red-light district — the mythical birthplace of jazz.