PROKOFIEV II: Gergiev and the LSO were breathtaking in the Fifth Symphony. |

Of the great international orchestras, perhaps the one that's most unfairly overlooked for, say, the Vienna or the Berlin Philharmonic is the London Symphony Orchestra. Yet a handful of the very greatest orchestral performances I've ever heard have been with the LSO. And now, thanks to the Celebrity Series of Boston, I can add another to that list: controversial but charismatic Russian maestro Valery Gergiev, at Symphony Hall, a stop on his multi-city tour, leading the LSO in Beethoven's Emperor piano concerto, with 32-year-old Russian virtuoso Alexei Volodin, and Prokofiev's best-known symphony, the just-post-war (1945) No. 5 — a program of music about heroism and heroics.

But "great" applied only to the orchestral part of the concerto. It opened with an incisive march that was more powerful and percussive than what you hear in most performances. The determined troops were entering — or leaving — the city. For a moment, Volodin's wooden, colorless, staccato playing — as if he were performing on a xylophone — seemed part of the conception. But it turned out he played everything the same way. Beethoven's magical, bell-like high notes sounded more like crickets. The orchestra gave the slow movement a caressing warmth, but Volodin remained metronomic, with no apparent interest in conveying a legato line. At the end of the slow movement, he played Beethoven's suspenseful transitional phrases into the Rondo Finale with an appropriate sense of expectation, but his dynamic level didn't change. Instead of white-hot and liberating, the pianism was tepid, whereas the orchestral troops sounded as if they were marching to an even great victory.

The Prokofiev Fifth was all LSO and breathtaking. Gergiev packed every phrase with meaning and nuance. This is also a piece about heroism, but it's subversively ambiguous. There's something queasy about the mal-de-mer harmonies in the first-movement march. Someone is having second thoughts about militarism. And we hear them in the nose-thumbing second-movement Scherzo, though by the end of the movement the nastiness isn't so funny — as if the satirist had been trampled and the army were mocking him by marching to his tune. The greatest ambiguity is in the finale, where victory and defeat, cheering and lamentation, are so interwoven you can hardly keep track of which is which — though Gergiev and the orchestra certainly did. The simultaneity of these emotional extremes was devastating. And exhilarating.

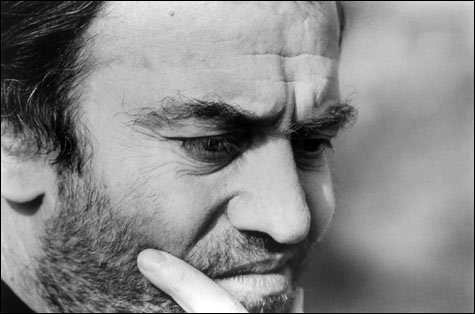

Gergiev has such an odd conducting style. His hands flutter and tremble. You don't know where the strong rhythmic pulse is coming from. His pinkies? His thumbs? His elbows? His wrists? The answer must be all of the above. And he gets such a beautiful sound from these magnificent players: great warmth in both the strings (antiphonally divided first and second violins, so you can hear their conversation) and those gloriously rounded horns (school of the great Dennis Brain), and so much color and attitude in the winds. And that sound is so well balanced, it's neither too thick nor too thin. The encore was the brief March from Prokofiev's opera The Love for Three Oranges, familiar, but unfamiliarly electrifying.

I have knowledgeable, sophisticated friends who think Gergiev is a fraud. One of them said to me before the concert: "I think he's a terrible conductor, and I'm here to learn what makes him terrible." By the end of this brilliant evening, I was wondering whether my friend had found any evidence to support his opinion.

Frequent Boston Symphony Orchestra guest conductor Charles Dutoit — the Philadelphia Orchestra's new music director, and the leader of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra — led a delightful program that included more Prokofiev: the Violin Concerto No. 2, which was bookended by Ravel's enchanting Mother Goose Suite and Stravinsky's sumptuous original 1911 orchestration of his ballet Petrushka. Dutoit had better luck than Gergiev with his young soloist, Georgian violinist Lisa Batiashvili. Still in her 20s, she is an elegant and impassioned virtuoso, and she gave Prokofiev's big tunes full force without wallowing, playing them with invigorating momentum. The bravura passages were dazzling without seeming show-offy. She never cracked a smile until the concerto was over, and then it was a beaut. Even without the usual violinist's dramatic lunges and gazes heavenward, she still got a thunderous ovation and countless curtain calls. Dutoit and the orchestra stuck with her, and the playing here, as in the exquisite Ravel and the micro-/macrocosmic Stravinsky (all the world's a Shrovetide Fair), scintillated.