FREE FOR ALL Maybe it was the beginning of the Age of Entitlement. |

Let me get this straight up front: I didn't go to Woodstock. But I was teaching a "student-initiated course" in pop-music history at Antioch College at the time, and a number of my students announced that they were going to miss a couple of classes because they had tickets to Woodstock that they'd bought through the mail. Although I was their age — or a little younger — I had no desire to join them, and I warned them that the thing would be crawling with cops. I'd lived in New York City a few years earlier, and my memories of the police were still vivid: the casual violence, the disregard of suspects' rights, the corruption, and the policeman who said, "Don't worry about us findin' dope if you don't have any; we've brought our own." The place would be crawling with these guys, I said. Make sure you have bail money.

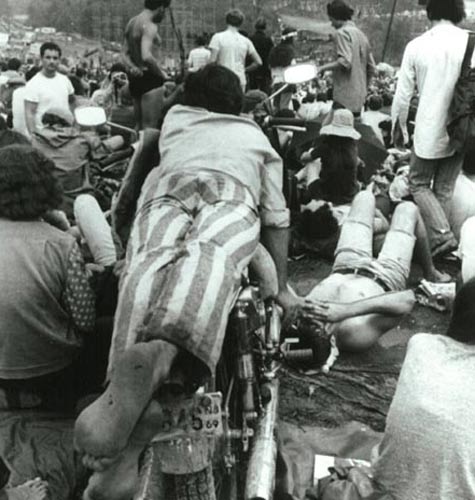

The students staggered back several days later than they'd expected, looking awful. I had been completely wrong about the cops, they told me, but that was about the only bright side of it. I'd caught a little of the coverage on television and in the New York Times, but that was mostly facts and figures. The story my students told was reported not from a helicopter passing overhead but from the (muddy) ground. There were way too many people there, they said, and you couldn't see or hear anything. There was no place to camp properly, and the whole thing, as one guy put it, "was like Boy Scout survival camp with dope." The grounds got filthier and filthier; since there was no place to dispose of garbage, it smelled. And when the members of their little group had found each other again and decided to leave, that too was almost impossible because of the mobs coming in. (It didn't help that they'd decided to hitchhike there and back, of course.) "And the worst of it was, we'd spent all this bread for tickets, and they just let everyone in for free. If we'd known that, we could've saved a lot of money."

They quickly forgot about Woodstock; meanwhile, I read a totally different version in Rolling Stone. This account, the result of a reporters' pool the magazine had sent to the festival, didn't ignore the sanitation and the crowd issues, but it played up a hippie-idyll angle my students seemed to have missed. What's more, the reporters had enjoyed backstage access and had gotten to hear the music very well, and they wrote about it with their usual skill. All of this interested me, because in addition to being passionately hopeful that a new world might be ushered in by a new generation of which I was a part, I'd had a couple of my own pieces accepted by Rolling Stone and was hoping to become part of it, too.

But I was disquieted by Woodstock then, and this feeling got more intense as time went on. There was the crowd's demand for a free festival. I'd done some concert promotion and watched others do it, and I knew it was hard work. I also knew musicians and was aware of how difficult their work could be. I didn't understand why these gate crashers, who I assumed were middle-class white kids (though crowd shots I've seen recently show far more black faces than would have been in a similar shot three years later), felt they had a right to free entertainment.

I was also put off by the juggernaut of hype that followed the event, hype that was generated by the media — including Rolling Stone — and snowballed as the release of Michael Wadleigh's 1970 documentary drew near. By the time the film came out, I was living in San Francisco and working for Rolling Stone, and my colleagues and I got to attend a screening in a big theater with a deluxe sound system. I wasn't aware at the time that much of what some people thought was the best music played at the festival — like the performances by the Band and the Grateful Dead — hadn't made it into the film. Neither was I aware that some of the music on screen — specifically the much-hyped debut of Crosby, Stills & Nash — had been re-recorded afterward. As a music critic, I was appalled by Ten Years After's interminable "Goin' Home," but not as appalled as I was by the many people I read and talked to who considered it the highlight of the film.