The current show in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum’s special-exhibition room, “Bellini and the East,” is another flickering jewel in the Gardner’s crown. The Bellini in question is not even the relatively famous Giovanni — who painted the Madonna of the Meadow and Sacred Allegory and The Feast of the Gods before being eclipsed, at least in the annals of art history, by Giorgione and Titian — but his older brother Gentile, who in his time (1430–1507) was most noted for an enterprise, the narrative frescoes in the great hall of the Doge’s Palace, that a great fire eradicated in 1577. It was Gentile who in 1479, at the conclusion of a peace between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, sailed to Istanbul in response to Sultan Mehmed II’s request for a Venetian painter. There he executed the portrait of Mehmed II that resides in the National Gallery in London and now anchors the Gardner show.

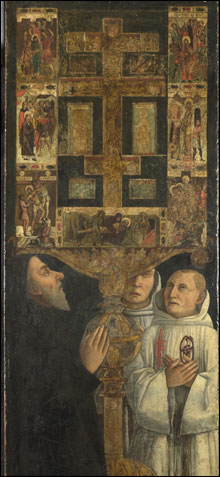

Just what else Gentile did during his 16 months in Istanbul is hard to confirm, despite the exhibition catalogue’s valiant attempt to attribute to his hand two of the four drawings the Gardner has assembled and also the museum’s own pen-and-watercolor work Seated Scribe. “Bellini and the East,” which will be up through March 26, isn’t really about Bellini; it’s about the pas de deux of trading and traducing that Venice and the Ottoman Empire engaged in following the fall of Constantinople in 1453. It’s about the convergence of Italian, Greek, and Muslim cultures in Venice. And about the efforts of Cardinal Bessarion, a Greek émigré, first to unite the Eastern and Western halves of the Church and then, having failed in that, to rally Venice and the rest of Italy behind the effort to retake Constantinople. The portrait of Mehmed II and Seated Scribe and the drawings are accompanied by two Gentile Bellini oil paintings, Cardinal Bessarion and Two Members of the Scuola della Carità with the Bessarion Reliquary and Portrait of Caterina Cornaro, and his Self-Portrait in black chalk plus a collection of medals portraying Mehmed II, a Virgin and Child by Giovanni Bellini, a Cretan Madonna and depiction of the Raising of Lazarus, Vavassore’s map of Constantinople, and an Ottoman box and Venetian salver. (The London version of “Bellini and the East,” April 12–June 25, will offer more, including Gentile’s Virgin and Child Enthroned and Giovanni’s The Doge Leonardo Loredan.)

But it’s Gentile Bellini who fascinates. The concluding phrase of his inscription on the portrait of Caterina Cornaro reads, “You see how great I am but greater still is the hand of Gentile Bellini that can portray me on such a small panel.” And some peculiarities about the encomium that Mehmed II wrote upon Bellini’s departure from Istanbul in January 1481 have raised suspicions that Gentile wrote it himself. He did not lack confidence. In that black-chalk self-portrait, the receding chin is more than offset by the shrewd eyes and tight-lipped mouth. It’s the look of the top painter in the Bellini family, the top painter in Venice, a loyal friend, an implacable enemy. He could be a character on The Sopranos, and not the kind that winds up sleeping with the fishes. Any doubts as to the identity of the subject are quashed by an accompanying medal executed by Vittorio Gambello with Gentile’s name on the rim: the faces are identical, and the particularity of both is striking.

But it’s Gentile Bellini who fascinates. The concluding phrase of his inscription on the portrait of Caterina Cornaro reads, “You see how great I am but greater still is the hand of Gentile Bellini that can portray me on such a small panel.” And some peculiarities about the encomium that Mehmed II wrote upon Bellini’s departure from Istanbul in January 1481 have raised suspicions that Gentile wrote it himself. He did not lack confidence. In that black-chalk self-portrait, the receding chin is more than offset by the shrewd eyes and tight-lipped mouth. It’s the look of the top painter in the Bellini family, the top painter in Venice, a loyal friend, an implacable enemy. He could be a character on The Sopranos, and not the kind that winds up sleeping with the fishes. Any doubts as to the identity of the subject are quashed by an accompanying medal executed by Vittorio Gambello with Gentile’s name on the rim: the faces are identical, and the particularity of both is striking.

Bellini’s Mehmed II is not the tough old bird of the medals (one of them said to have been designed by Gentile) but a frail, worn-looking ruler. Mehmed’s head is tilted down ever so slightly, so that his nose seems longer and his face longer and thinner, and his chin disappears into the fuzzy length of his beard. His head is dwarfed by his turban; his entire body dissolves into his robe. He’s defined by the magnificence of his office — the framing arch and parapet, the cloth of honor — even as it consumes him. It’s not a conventionally flattering portrait; only a very wise ruler would have appreciated it. The same is true of Bellini’s portrait of Caterina Cornaro, which emphasizes her small features and short, thick neck and massive upper body but also the intelligence and achievement of a woman who at age 18 married the king of Cyprus and upon his death became that island’s ruler. It’s a cartoon and not an idealization, yet it pays tribute in the degree to which it details the tiny diamond pattern on her cloth-of-gold dress. Her expression is forthright; like Gentile in his self-portrait, she knows who she is and makes no apologies.