ENCHANTED APRIL: Emotional dead wood blooming in spite of itself.

|

What one most remembers from the 1992 Mike Newell film Enchanted April is the beauty duel between Polly Walker and the scenery. Matthew Barber’s stage adaptation of Elizabeth van Arnim’s 1922 novel, which was nominated for a 2003 Tony Award, can’t hope to compete with the film in serving up the “wisteria and sunshine” that draw four sensually deprived Englishwomen to Italy in the devastating wake of World War I. But it does a better job of capturing the book’s post-war melancholy, which thaws along with class distinctions in a rented castle by the sea. And at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, where Normi Noël’s production continues in repertory through September 2, a sensitive and competent ensemble turns on both the sadness and the heat as four unlikely “sisters” discover their inner rejuvenators. Even Rachel Gordon’s set blooms, sprouting garlands and urns full of flowers during intermission.The play begins to the tune of English rain, with Diane Prusha’s slightly dotty, sensibly shod Lotty telling (for the first time) the book’s story of a man who plants his walking stick on a new property to mark the place where he intends to plant an acacia, then returning in spring to find that the stick itself has taken root and sprouted — and that is it indeed an acacia. The play is a similar fable, in which emotional dead wood blooms in spite of itself. The charming story, however, is slow getting off the ground, with act one taking the form of nine short scenes during which the meek but unstoppable Lotty, inspired by a newspaper ad for the Italian castle to let (and by her own prescient visions), bulldozes Ladies’ Club acquaintance Rose Arnott into signing on, then rounds up languid flapper Lady Caroline Bramble and dictatorial widow Mrs. Graves to complete the party. And, of course, we meet the husbands who are making Lotty and Rose unhappy: condescending lawyer Mellersh Wilton and party boy Frederick Arnott, who distresses his religious wife by writing salacious biographies under a pen name. Although well sketched and amusing, the act seems fragmented and the English dreariness in which it unfolds all too real.

Act two brings not only warmth but cohesiveness to the material — along with combustible Italian retainer Costanza, played by Rachel Siegel as an oddly young and blonde but credibly unilingual spitfire who is also a comfort. Each of the women at San Salvatore Castle is nursing a heartache, Rose for her errant husband and the loss of a child, Lotty for her disappointing marriage, Lady Caroline (as she graciously permits herself to be called, omitting her sir name but not her title) for a love whose loss no amount of gin, jazz, and modernity can assuage, and the literarily connected Mrs. Graves for the less ossified life her rigidity has kept her from living. (Barber changes the names of some of Arnim’s characters.) But eventually all are pulled into the maelstrom of Lotty’s ditzy determination to kiss “before” goodbye and forge an “after” into which to plunge headlong. And this being 1922, when women were arguably defined by men, the guys, including the jovial castle owner to charm Mrs. Graves and rekindle Lady Caroline, must show up to smell the sun, sex, and flora.

Shakespeare & Company fields a cast led by some of its stalwarts, not all of whom seem right for their roles, but they treat the material with the requisite light touch, missing neither its humanity nor its comedy. The baby-voiced Prusha’s Lotty, thundering about in old-fashioned bathing costume as she attempts to rouse her companions, is a shy matron out of whom a girl is popping. Tod Randolph’s Rose is at first a woman almost startled by her unhappiness; decked out in white under the Italian sun, she gradually, wonderingly, discards her prudishness. Elizabeth Ingram’s Mrs. Graves is less of a dragon than the one Joan Plowright played in the film (there’s more Maggie Smith about her), but her timing is as formidable as she is. And Corinna May, her sylphlike form draped by designer Govane Lohbauer in a series of diaphanous outfits of the era, is a pitch-perfect Lady Caroline, flaunting her beauty even as she shrugs off her looks. Malcolm Ingram’s Mellersh is less overbearing than just unimaginative, and Dave Demke’s dapper Frederick receives his wife’s transition from “disappointed madonna” to loose-tressed vixen with a dazed but deeply satisfied grace.

SAMURAI 7.0: A droll if also earnest comment on itself.

|

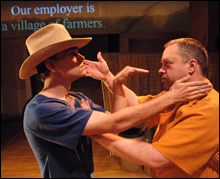

Beau Jest Moving Theater’s Samurai 7.0: Under Construction (at the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts through June 24) has also been to the movies. The inspiration for the 75-minute theater piece is the epic 1954 Akira Kurosawa film Seven Samurai, which it more or less duplicates with eight actors, bamboo props from Pier One, and projected supertitles. As director Davis Robinson points out in a program note, the film’s story — in which the inhabitants of a farming village in feudal Japan hire unemployed samurai to defend their town against marauding bandits — is simple. But Beau Jest is out less to tell that tale than to prove it can, using ingenious low-tech methods that have been all but trampled in this Phantom-of-the-Opera-meets-multimedia age. Hence the show is a droll if also earnest comment on itself.Founded in 1984 by then Emerson College theater professor Robinson, the troupe (best known for the Elliot Norton Award–winning Krazy Kat) has been dormant for seven years, Robinson having moved on to Bowdoin College in Maine. Afforded a sabbatical, he proves himself the theater-making junkie he is with this clever comeback, which is fun to watch but not easy to fathom the point of. It seems less an homage to Kurosawa than to roughhewn theater, randomly referring to Shakespeare, in particular the Chorus of Henry V and the “rude mechanicals” of A Midsummer Night’s Dream preparing “Pyramus and Thisbe” for the Duke. But Beau Jest is no bunch of amateur rubes whose crude efforts exist to be made fun of by royalty. Its use of little is witty and graceful, if hardly adequate to replicate action filmmaking of the 1950s — though the brevity of Samurai 7.0 does stand as a gentle suggestion that, even with all those galloping bandits and thwacking battles in the rain, Kurosawa’s film didn’t need to be three and a half hours long.