Bob Dylan’s music isn’t the first thing you’d think of as the basis for a dance show. But Twyla Tharp has never been daunted by long odds — in fact, she seeks out gambits that would terrify any reasonable person. Instead of trying to repeat the scheme that brought her Broadway success in the all-dance Movin’ Out, which she set to the music of another pop star, Billy Joel, she ups the ante in The Times They Are A-Changin’, which opened at the Brooks A

tk

inson Theater in New York last Thursday. This time the venture misfires.

THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’: The show diminishes the music, even though the music is its life blood.

|

As with Movin’ Out, Tharp developed the Dylan show by assembling about two dozen songs from the total œuvre. From these she created a story line and some characters, then translated them to the stage via dancers, singers, and a band. Tharp was confident that the action and the music would tell the audience everything it needed to know without benefit of dialogue. She’d created half a dozen ballets to popular music the same way.

I think her original notion for Times was to have the dancers do the singing. Although there are plenty of Broadway actors who can do both, Tharp’s dance is no shuffle-ball-change proposition. She wanted dancing specialists, daredevils. Others would have to carry the vocalizing. In Movin’ Out, the split was handled smoothly with pianist/singer Michael Cavanaugh and the band suspended on a platform above the stage, providing musical accompaniment for the dance action. In Times, Henry Aronson leads a small band (arrangements by Michael Dansicker and Dylan) nestled up in the air again. They don’t sing, though.

Three actors carry the vocal responsibilities and the wispy plot while the dancers gyrate around them. For me, this caused an impasse — either get into the songs or watch the dancing. The two levels of storytelling, if that’s what they are, don’t complement each other, and both are insistently demanding of your attention.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

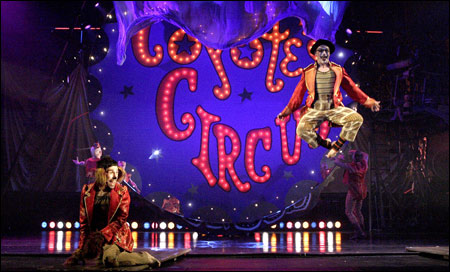

Mean old one-legged Captain Ahrab (Thom Sesma), the owner of a seedy traveling circus, is locked in Oedipal conflict with his son, Coyote (Jason Wooten in the press performance that I saw Wednesday — Michael Arden played the role in the first cast). Cleo (Lisa Brescia), a waif of indeterminate age, is also conflicted, about whether to hang around Ahrab’s room or run away with Coyote. Various Dylan songs are applied to describe their states of mind. Eventually Ahrab is dispatched, and instead of running away, Cleo and Coyote take over the circus, determined to make it prettier.

A note in the program nails the setting as “sometime between awake and asleep” and describes the piece as a “fable.” A brief note explains Ahrab’s tyrannical greed, Cleo’s naïveté, and Coyote’s separation anxiety. But what this is, I think, is a pageant of Tharp’s master plots put together. Life as chaos, a three-ring circus surrounded on all sides by Death. We have the dysfunctional family struggle, the rambunctious escape fantasy, and the resolution when the characters somehow grow up.

Ahrab snarls and cracks his whip like some horrid schoolmaster out of Dickens. Coyote looks like a high-school kid in the 1950s. Cleo wears a red silk slip and could be a pawn or a prostitute, or — another of Tharp’s tropes — the Little Match Girl. Except for the more or less contemporary Cleo and Coyote, Santo Loquasto’s sets and costumes suggest a bunch of mid-19th-century Gypsies camped somewhere in the depths of a Transylvanian forest.

Decked out in dozens of tawdry costumes, the seven clown acrobats show off their skills almost at random. They bounce across trampolines that span the front and back of the stage. They impersonate animals. They do flips and contortions, walk on stilts, negotiate a tightrope. They walk on their hands. They form a plink-plank washboard band. They jump rope. Occasionally they do a dance number.

Then there’s the music. Learned people have written tomes on the metaphysics of Bob Dylan and rhapsodized about the way he changed their lives. I’m no Dylan expert, and after one viewing I can’t determine whether the songs add poetic substance to Tharp’s masquerade. But it seems to me the show diminishes the music, even though the music is its life blood.

Dylan’s songs don’t have the driving momentum of Billy Joel’s; they don’t produce a throbbing dance impulse in the audience. They’re really literary expressions made compelling by his own style of delivery, his tight, raspy tenor lapsing from song to speech, abandoning the melodic line then sliding back to it, as if music alone couldn’t express the rage, the regret, the irony.