.jpg)

OLD STAPLE, NEW APPRECIATION: The Brattle Theatre is one of Harvard Square’s few remaining landmarks.

|

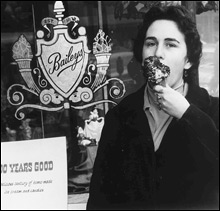

Forty years ago, hard to imagine, I was still a graduate student, trying to live on a $1500-a-year scholarship, a teaching fellowship, and grading papers for large courses at $5 a head (you could just about manage that 40 years ago). Harvard Square was very different then. There were record stores (plural), with especially knowledgeable salespeople at the Harvard Coop (Helge) and Minute Man (Bernie). Three cafeterias stayed open all night: the Hayes Bickford (a/k/a “the Bick”); Albianis (near the UT, the University Theatre, now the Harvard Square Theatre; then it had only one large auditorium); and the Waldorf. For lunch I gorged on brown paper bags full of the juiciest big-bellied fried clams and the most delectable curlicue French fries this side of Brussels, at Mike’s Place on Dunster Street, and on ice cream at Brigham’s (“Could I have a vanilla cone?” I asked the server once; “Easier said than done!” he replied with enthusiasm) or a vanilla frappe with an egg in it at Bailey’s.

Harvard Square’s elegant restaurants were the Blacksmith House, on Brattle Street (site of Longfellow’s “spreading chestnut tree”), where the wait staff were refugees and the pastries were heavenly; Chez Dreyfus, on Church Street, which served rabbit; and Chez Jean, on Shepard Street, where you could afford a superb French dinner. At the Harvard Faculty Club, horse steak was the cheapest item on the menu. There were cream-cheese-and-caviar sandwiches on bulky rolls to go at Elsie’s on Mt. Auburn Street, sublime hamburgers at Mr. Bartley’s, and hundreds of varieties of imported beer at the Wursthaus. Cold lazy man’s lobster was only $2.50, when the Coach Grill on Boylston Street (now JFK Street) had it on special. And the terrific hot dogs at the tiny Tastee, right in the middle of Harvard Square, were even cheaper. Only the Chinese-restaurant situation was as dire then as it is now. We had to wait for Joyce Chen, at her fancy new restaurant on Memorial Drive, to introduce us to sizzling Sichuan cuisine.

At the Brattle Theatre, the entire audience shouted (correctly), “Play it, Sam” and “I’m shocked, shocked” along with Humphrey Bogart and Claude Rains during the regular Bogart festivals. Then everyone would go a few steps for the perfect martini at the Casablanca or coffee at the Blue Parrot, or for fancy soaps or aromatic candles at Truc, in the same building.

.jpg) Storefronts hadn’t yet been boarded up after student protest riots. Brine’s was the sporting-goods store of choice, Dickson Brothers the place for hardware. I still have a three-inch-wide bright yellow tie dotted with pink roses from Krackerjacks. And there were countless bookstores, new and used, wherever you turned. Pangloss, the Star, Schoenhof’s for foreign books (fortunately still in business), later the Temple Bar. What a shock when Mr. (did I ever learn his first name?) Rosen’s beloved Mandrake moved from JFK to Story Street. The Grolier was not only a place where you could find practically every book of poems in print, it was also where you could hang out with other poets, or overhear the people sitting on owner Gordon Cairnie’s couch talking about poetry. Robert Lowell was teaching at Harvard and everyone — anyone (you didn’t have to be a Harvard student) — who knew about his weekly “office hours” could bring their poems to an airless, windowless, smoke-filled basement room under Harvard’s Quincy House dining hall. Such “local” poets as Frank Bidart, Robert Pinsky, and Gail Mazur were among the regulars, as were such talented undergraduates as Jonathan Galassi (now editor-in-chief at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) and controversial biographer and memoirist James Atlas. After “office hours,” we’d follow Lowell to the Iruña (just closed this year) for Basque omelets and sangria and try to stop him from picking up the check.

Storefronts hadn’t yet been boarded up after student protest riots. Brine’s was the sporting-goods store of choice, Dickson Brothers the place for hardware. I still have a three-inch-wide bright yellow tie dotted with pink roses from Krackerjacks. And there were countless bookstores, new and used, wherever you turned. Pangloss, the Star, Schoenhof’s for foreign books (fortunately still in business), later the Temple Bar. What a shock when Mr. (did I ever learn his first name?) Rosen’s beloved Mandrake moved from JFK to Story Street. The Grolier was not only a place where you could find practically every book of poems in print, it was also where you could hang out with other poets, or overhear the people sitting on owner Gordon Cairnie’s couch talking about poetry. Robert Lowell was teaching at Harvard and everyone — anyone (you didn’t have to be a Harvard student) — who knew about his weekly “office hours” could bring their poems to an airless, windowless, smoke-filled basement room under Harvard’s Quincy House dining hall. Such “local” poets as Frank Bidart, Robert Pinsky, and Gail Mazur were among the regulars, as were such talented undergraduates as Jonathan Galassi (now editor-in-chief at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) and controversial biographer and memoirist James Atlas. After “office hours,” we’d follow Lowell to the Iruña (just closed this year) for Basque omelets and sangria and try to stop him from picking up the check.

ADVERTISEMENT

|

SWEETER DAYS: Bailey’s served vanilla frappes with an egg.

|

Across the river were more movie theaters, and at Symphony Hall, music director Erich Leinsdorf was introducing major works (like Mahler’s Sixth Symphony) to Boston Symphony Orchestra audiences. He was a dull conductor who made exciting programs. The old Opera House was already torn down, but Sarah Caldwell and her Opera Company of Boston were presenting stunningly inventive — and historic — productions at rundown old movie theaters or gymnasiums at Tufts and MIT. She gave the American premieres of major works like Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron (which finally had its first BSO performance only a few weeks ago), and the first Boston production of Berg’s decadent Lulu, with black-and-white sets like newspaper clippings — productions that made Boston the focus of international attention and admiration. Caldwell virtually discovered Plácido Domingo, and the reigning diva here was Beverly Sills before anyone else knew about her. Caldwell gave Sills her first chance to sing 18th-century opera, shortly before her dazzling, tongue-in-cheek singing of Cleopatra in Handel’s Giulio Cesare at the New York City Opera made her a superstar. Less than a decade later, she was still singing with Caldwell and giving her first Symphony Hall recital for the Celebrity Series.

Versatile baritone Donald Gramm and one of Serge Koussevitzky’s favorite contraltos, Eunice Alberts, were other Caldwell regulars. Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, and Shirley Verrett sang roles for Caldwell before they sang them at the Met. And every year, the Met itself came to town, bringing to the Music Hall (now the Wang Theatre) or to a makeshift stage at the Hynes Auditorium their fabulous or terrible touring productions. Harvard Gilbert & Sullivan featured dazzling performances by soprano Susan Larson, the best operetta singer I’ve ever heard, balancing on a tightrope between high comic style and real feeling. She went on to play leading roles in almost every production of Mozart and Handel conducted by Emmanuel Music’s Craig Smith and staged by Peter Sellars, who picked up the torch from Caldwell and kept Boston a world opera center. Early music hadn’t yet caught fire, but the Camerata’s Joel Cohen was already playing his lute and building excitement about the pre-Classical classics.