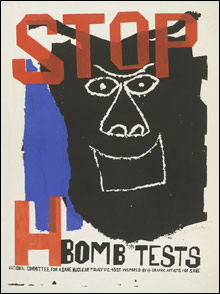

STOP H BOMB TESTS Ben Shahn’s 1960 anti-nuke fundraising poster remains striking and fresh. |

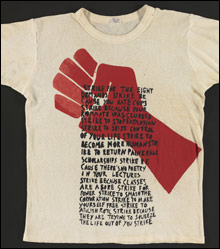

In 1969, Harvard University students rallied to support the creation of a black-studies program and protest the Vietnam War, the presence of ROTC on campus, and the university’s expansion into surrounding communities. Events boiled over when protesters commandeered University Hall and police, on administration orders, roughly evicted them. Hotheads on all sides prevailed. A T-shirt printed at the Harvard Strike Poster Workshop in the midst of the hubbub, and included in the exhibit “Dissent!” at Harvard’s Fogg Museum, bears a blocky red fist and a wonderful long list of student grievances: “Strike because you hate cops . . . strike to become more human . . . strike because there’s no poetry in your lectures . . . strike to smash the corporation . . . strike to abolish race . . . strike because they are trying to squeeze the life out of you.”“Dissent!” is a fiery greatest hits of five centuries of such protest art. Here’s Édouard Manet’s circa 1871 lithograph of French soldiers firing into a Paris crowd. There’s a 16th-century Reformation woodcut complaining that the pope is playing us for suckers; we see a wolf wearing a pope hat seducing sheep away from Jesus. A 1770 knockoff of a Paul Revere broadside (who was knocking off somebody else) shows dastardly redcoats gunning down Bostonians in what became known as the Boston Massacre. The 62 prints and publications offer a who’s who of art rabble rousers: Honoré Daumier, Francisco de Goya, Käthe Kollwitz, José Guadalupe Posada, Pablo Picasso, Joseph Beuys. It’s important that we see and study this stuff, but the challenge for institutional exhibits — a challenge curator Susan Dackerman doesn’t solve — is how to embrace protest art without neutralizing it.

The works that retain the most power to inspire are the Technicolor posters of Sister Corita, a Los Angeles Roman Catholic nun and college art teacher who left the sisterhood and moved to Boston in 1968 — where her legacy is most prominent as the designer of those rainbow stripes on the Boston Gas tank along Route 93 in Dorchester. The show offers six eye-popping hot-pink, blue, and yellow screenprints from 1969 that condemn the Vietnam War, poverty, and the oppression of African-Americans. Corita, who died in 1986, had a pop sensibility, often appropriating and rejiggering corporate logos, package designs, and advertising slogans. Here she incorporates images of a mourning Coretta Scott King, a smiling Eugene McCarthy, a black boy crying on the cover of Life magazine, a captured Vietcong fighter from the front of Newsweek. A Passion for the Possible takes a quote from Yale chaplain and activist William Sloane Coffin: “Realism demands pessimism, but hope demands that we take a dim view of the present because we hold a bright view of the future, and hope arouses as nothing else can arouse a passion for the possible.” Corita creates sparks by combining such subtle and moving texts — they often sound like something e.e. cummings might have written — with her crackerjack eye for color, typography, and composition, an eye that’s apparent here as she creates rhythm and emphasis by switching back and forth between mechanical typefaces and her handwritten script.

Ben Shahn’s 1960 anti-nuke fundraising poster — with its sketch of a cackling black death mask flanked by a blue stripe (a bomb?) and the slogan, in urgent capital letters, “STOP H BOMB TESTS” — remains striking and fresh. Jenny Holzer’s five Inflammatory Essays posters, originally pasted up on Manhattan streets between 1979 and ’82, are powered by their tone, a menacing voice from some invisible force keeping an eye on you. One of the more, uh, upbeat ones warns: “All you rich fuckers see the beginning of the end and take what you can while you can . . . know that your future is with us so don’t give us more reason to hate you.”

STRIKE! The challenge for institutional exhibits like this is to embrace protest art without neutralizing it. |

Andy Warhol contributes a 1964 screenprint of police siccing dogs on blacks who are protesting segregation of schools and lunch counters in Birmingham, Alabama, and also a poster for the 1972 presidential election of a sickly green Richard Nixon with the punch line “Vote McGovern.” It’s one of the few times Warhol comes right out and says just what he means. Could his images of Jackie Kennedy, electric chairs, and hammer-and-sickles be more than just a reflection of pop culture, as they are generally understood? Could they have also been chosen for their political meaning?The show’s recent works are mostly lame. Like the Warhols, they’re mostly art-gallery collectibles, often by art stars working out of character, rather than street-smart agitprop. Raymond Pettibon tosses off a print of a bloody eagle bursting apart. Fred Tomaselli paints an exploding psychedelic mask over a newspaper photo of Bernard Ebbers after he’d been found guilty of corporate fraud. Take that!