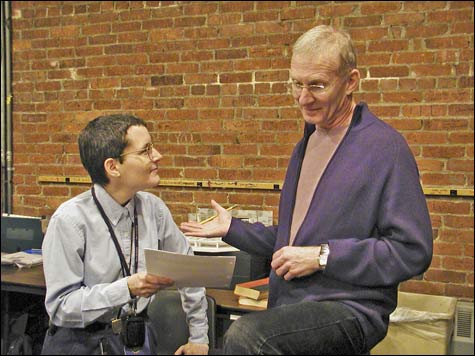

NON-EXPRESSIVE EXPRESSION: McEleney [right] with stage manager Buzz Cohen.

|

When Thornton Wilder’s Our Town hit the stage in 1938, mainstream Broadway ticket holders finally knew the thrill of theatrical surprise that artsy appreciators of the avant-garde had been crowing about. Instead of props and realistic set, actors pantomimed activities such as placing a pie in an oven. Two characters atop stepladders and facing the audience were supposed to be facing each other through bedroom windows. One of the actors was chatting up the audience through the fourth wall, narrating the action and occasionally stepping in to play a role.

But that was then and this is now. Nearly three quarters of a century later the novelty is old hat, and the current Trinity Repertory Company production (through March 4) has the difficulty of freshening up one of American theater’s most frequently performed classics.

“So my challenge as a director is how do you get that same sense of: ‘Oh, this is startling!’ in our post-Brechtian, post-Adrian Hall, post-Amanda Dehnert world?” says Brian McEleney, wearing his director’s hat as he discusses the problem during a rehearsal break.

“As I said to Michael McGarty, my designer,” he continues, “people are seeing that back wall of the Chace Theater so many times, how can we get them to not look at this play and say, ‘Oh not that again!’ ”

His solution is simple and straightforward: putting the backstage onstage. Arriving at the theater their mandatory 30 minutes before curtain, the actors will go to open-fronted dressing rooms behind the upstairs theater performance area, where we can see them changing from their street clothes and conversing among themselves. The idea is for us to see the community of actors in the same offhanded way that Wilder acquaints us with the community of Grovers Corners.

Our Town employs a narrating Stage Manager, although the actor is never so identified except in the printed script. McEleney is having Barbara Meek take that role, since as the senior member of the acting company she has a similar relationship to it as the Stage Manager does to the New England town.

Another decision the director made was to not have the actors speak in what he calls “the Pepperidge Farm accent.”

“I did consciously steer them away from the clichéd New England accent,” he says. Instead, he’s having them “try to find that New England stoicism through behavior rather than through the veneer of that sound, which can head toward the sentimental. These people aren’t folksy in that way. They’re reserved.”

That last matter is very important to McEleney, since the playwright made a point of setting the play, he notes, “in an intentionally non-expressive culture.” Thornton Wilder was raised in Wisconsin, not in Peterborough, New Hampshire, which he visited a few years before writing Our Town and upon which the play is regarded as being based.

“A challenge for all the actors was to find this sense of New England reserve — that is really, really important,” he says. “These people don’t spill their guts. They don’t tend to get very outwardly emotional. They have an extremely developed sense of privacy and giving other people their privacy. We certainly as actors are more used to letting it all hang out and expressing ourselves.

“One of the great geniuses of the play is that he makes the two main protagonists kids, who haven’t been entirely socialized into this world of reserve yet — so they’re kind of in slight conflict with it,” he adds.

That emotional tension of the young Emily and George (Susannah Flood and Eric Murdoch), who eventually marry, could be seen as a small-scale reflection of the tension in the world at large in 1938, in the midst of the Depression and with Germany’s invasion of Poland in the works.

Our Town is often seen as harking back in troubled times to a Golden Age. But McEleney thinks that Wilder’s motivation was different. “He could have put this play anywhere and he clearly, consciously chose the least interesting people he could make, the least interesting place — on the outside. But these people are incredibly fascinating. And that’s kind of the point of the play.

“One of the things he’s saying, certainly, is that the history of human beings is a history of people waking up in the morning, making their breakfast, greeting their spouses, sending their children off, going to work, coming home, going to bed,” the director says. “We think of history as wars and elections, but what really holds human beings together is everyday life. That’s what we all have in common, everyone on the planet.”