The race for Marty Meehan’s congressionalseat is running below the radar, but it could hold the answers to a couple of burning political questions

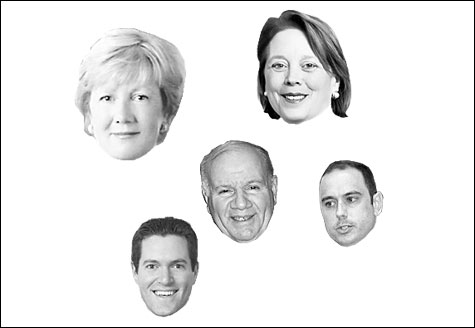

Clockwise from top left: Donoghue, Tsongas, Eldridge, Finegold, Miceli

|

|

LEADING LADIES

Signs would certainly suggest that, on the national stage, a political family heritage is as valuable as ever (see: George W. Bush), and that women can successfully exploit the connections. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, whose father was a congressman from Maryland, is one of four daughters of former members of Congress now serving. Four widows of former members are also in Congress. And of course, Hillary Clinton became a US senator, and may become president.

But in Massachusetts, the last two women elected to Congress — Margaret Heckler, who served from 1967 until 1983, and Louise Day Hicks, who served one term beginning in 1971 — made their own names. The same is true of other prominent elected women in the state, including Senate President Therese Murray and Attorney General Martha Coakley.

|

The upcoming special election to determine a successor to Marty Meehan — who, after 15 years in Congress, is leaving to become chancellor of UMass Lowell — may lack the glitz of the Clinton vs. Obama showdown and the nastiness of the Romney/McCain/Giuliani brawl. But the September 4 Democratic primary does have compelling interest beyond the borders of the Fifth Congressional District, since front-runner Niki Tsongas, the widow of the late senator and one-time presidential aspirant Paul Tsongas, may serve as a litmus test for two developing political uncertainties:

1) Whether American politics will continue to take on a royalist flavor — with the likes of the Kennedys, Bushes, Cuomos, and Clintons besting those who lack recognizable names. And,

2) Is Tsongas — who, if she were to win, would become just the fourth woman that Massachusetts has ever sent to Washington — part of a rise in female power within the Democratic Party, along with stars such as Hillary Clinton and Nancy Pelosi?

Tsongas’s four opponents for the Democratic nomination complain that her name recognition alone shouldn’t decide the race. And that’s a reasonable, but futile, point to make in a state that for 200 years has swooned over the scions of Adams, Davis, Everett, Lodge, and O’Neill.

On the other hand, this is not your grandfather’s Massachusetts, and none of the state’s leaders — including Governor Deval Patrick, Senate President Therese Murray, and House Speaker Salvatore DiMasi — was born with a silver gavel in his or her hand.

Congressman Barney Frank, a Tsongas supporter (who, coincidentally, defeated the last woman to represent Massachusetts in Congress, Margaret Heckler, when their districts were combined after the 1980 Census cost the state a seat), has said that this race will capture national attention as a referendum on the Iraq War and the 2006-elected Democratic Congress. But so far, the attention has settled on two decidedly different issues: Tsongas’s late husband and her gender.

Careful references

Tsongas is unabashed about playing the gender card, even though one of her chief rivals is Eileen Donoghue, a former mayor of Lowell. (The other Democrats running are state representatives Jamie Eldridge, Barry Finegold, and Jim Miceli.)

Despite Donoghue’s presence, Tsongas has gained the endorsement and fundraising support of EMILY’s List, which backs female candidates nationally, and the Massachusetts Women’s Political Caucus. Many of the most prominent women in Massachusetts political circles also have endorsed Tsongas, including Kitty Dukakis, Patricia McGovern, Swanee Hunt, Evelyn Murphy, Cheryl Jacques, Angela Menino, Barbara Lee, Lois Pines, Margaret Xifaras, and Andrea Silbert, as well as three state senators and five state representatives.

In June, her campaign gathered 350 women in support of Tsongas, including businesswomen and community activists. There are “Tsisters for Tsongas” events. And the Lowell headquarters of her campaign feature prominent reminders that the state has had more than two decades of exclusively male representation.

Tsongas’s campaign is, however, far more discreet about referring directly to her late husband. He is mentioned in few materials, and his instantly recognizable, cherubic Greek face is nearly absent. The TV ad she’s been airing speaks of her father, a World War II hero, more than her late husband.

But indirect references are constant. Tsongas is actively trading on Paul’s popularity, boasting of the Washington connections she made during his time in office and while he ran for president in 1992. She paints herself as his political partner — one campaign promo piece even says that, in 1978, “Paul and Niki won” the election for US Senate. And she took some grief for a comment made during a recent debate, which some have interpreted as her claiming to have, as Paul’s wife, represented the district and then the state in Washington, DC.

But today’s Democratic Party, which is rallying behind Clinton, has largely accepted the legitimacy of the “political spouse” experience. Political partners such as Elizabeth Edwards are becoming the norm; spouses disengaged from their husband’s work, such as Dr. Judy Dean (wife of Howard), are a rare curiosity.