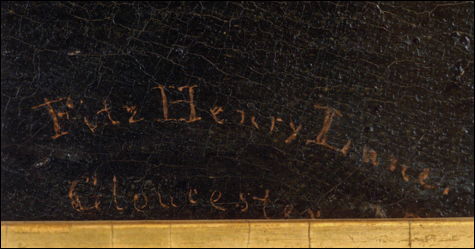

THE SIGNATURE: Even if a friend did sign this, you’d think he’d have got the name right.

|

|

“Fitz Henry Lane & Mary Blood Mellen: Old Mysteries and New Discoveries” | Cape Ann Historical Museum, 27 Pleasant St, Gloucester | Through September 16

|

In 2004, Jane Walsh of Gloucester’s official archives committee did a quick Web genealogy search on 19th-century Gloucester marine painter Fitz Hugh Lane. Her inquiry was prompted by a lecture in which eminent art historian John Wilmerding had discussed one of the persistent Lane mysteries: why, when he was a young boy, did the artist change his name from Nathaniel Rogers Lane.

Up popped Lane’s request to change his name to Fitz Henry Lane. Walsh and her committee comrades figured “Henry” must be a mistake, a typo maybe. Still, it was an error they came across with some frequency in Lane records. And so they visited the state archives in Boston to look at Lane’s actual petition.

“And sure enough, there it was: Nathaniel Rogers Lane writing in to ask if he could have his name changed to Fitz Henry Lane,” says co-chair Sarah Dunlap. They realized that Lane had always been Fitz Henry. Fitz Hugh was the error.

The report of the discovery by Dunlap and Cape Ann Historical Museum librarian/archivist Stephanie Buck in the February 2005 issue of the Essex Genealogist heralded a new body of Lane research. Last year, Gloucester historian James Craig published Fitz H. Lane: An Artist’s Voyage Through Nineteenth-Century America (History Press), a biography that provides new insight into Lane’s involvement with the Transcendentalist, Spiritualist, and Temperance movements. Craig even turns up a brief mention that could be proof that Lane taught New Bedford marine painter William Bradford. Also last year, the staff at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston made the case that Lane used a lens known as a camera lucida to help him trace the contours of landscapes onto his sketches and paintings. This fall, Dunlap and Buck are planning to publish a book on Lane’s years in Gloucester. Wilmerding, meanwhile, has assembled 50 artworks for the Cape Ann Historical Museum’s current exhibit “Fitz Henry Lane & Mary Blood Mellen: Old Mysteries and New Discoveries,” which looks at Lane’s artistic relationship with one of his chief students.

CLIPPER SHIP “SWEEPSTAKES”: What stands out is Lane’s attention to the way light breaks

through clouds and falls on sails and waves.

|

And yet, the discovery that we’ve had Lane’s name wrong since at least 1913 has prompted questions about what else scholars have gotten wrong about him. Notably what Wilmerding has gotten wrong. He is part of a handful of scholars (others include Barbara Novak and Theodore Stebbins Jr.) who’ve been credited with pioneering scholarship of 19th-century American art. Wilmerding’s “find” was Lane, one of several artists who had fallen into obscurity with the rise of French Impressionism and Modern art. Lane’s work now commands top prices — Skinner Auctioneers in Boston got $5.5 million for Manchester Harbor back in November 2004.

Wilmerding, a descendant of major art collectors, began the research that would lead to his first book on Lane, which he published in 1964, while studying at Harvard. He was fortunate to be among the first scholars to examine the collection that Maxim Karolik, a pioneering collector of 18th- and 19th-century American art, had begun donating to the Museum of Fine Arts in 1938. And at the nearby Cape Ann Historical Museum, he had access to the largest collection of Lane works anywhere.

Wilmerding went on to teach at Dartmouth and Princeton. He was a curator and deputy director at Washington’s National Gallery of Art. His 1971 Fitz Hugh Lane (Praeger) has been the standard monograph on the artist; he also organized the catalogue for the 1988 Lane survey exhibit at the National Gallery and the Museum of Fine Arts. He contributed books on Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, and numerous other American artists. He’s now a leading adviser to Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton, who’s been buying up 19th-century American masterpieces for a planned museum in Arkansas.

“Fitz Henry Lane & Mary Blood Mellen” is an intriguing scholarly exhibit that hangs Lane’s seascapes and Mellen’s copies side by side. It opens with Clipper Ship “Sweepstakes” (1853), one of two known Lane paintings signed “Fitz Henry Lane.” Wilmerding may have inherited the “Hugh” mistake, but he didn’t question it when he was asked to examine this canvas and its signature in 1993. He said he believed the painting was by Lane with “no additional hands at work,” and that Lane’s close friend (and executor of his estate) Joseph Stevens or someone else might have signed it “Fitz Henry.” It’s not a convincing explanation: we were asked to believe that, first, that a close friend “signed” the painting, and, second, that this friend couldn’t even get the artist’s name right.