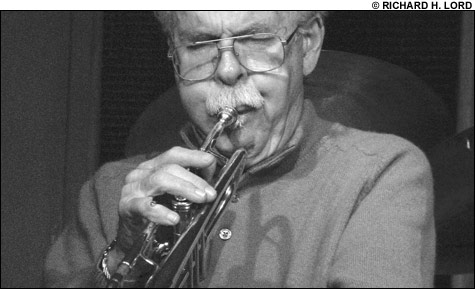

THE MASTER: For Pomeroy, jazz was an intimate personal relationship.

|

Maybe there have been better musicians in Boston than Herb Pomeroy — maybe — but no musician has been more loved. Talk to a handful of Pomeroy’s colleagues around town and you always come up with the same story: no bandleader got better results from his charges than Pomeroy. He did it with his supreme musical knowledge combined with a deep respect for the people who played for him — whether they were part-time student musicians or 30-year pit-band veterans.

Pomeroy — who died on August 11, at the age of 77, from cancer — was a fixture on the Boston scene for more than half a century. A Gloucester native, he famously dropped out of Harvard after a year in order to play jazz. He studied at Berklee before it was Berklee. (It was called Schillinger House.) By the age of 23, he was playing trumpet alongside Charlie Parker in that titan’s Boston gigs (and “terrified,” according to one friend’s account). By 1955, he was teaching at Berklee, where he was a faculty member until his retirement in 1995. He also had a long teaching relationship with MIT, where he founded the MIT Festival Jazz Ensemble in 1963. By the time of his death, he was probably the most renowned teacher of jazz performance in the world. With a few of his colleagues at Berklee, he virtually invented jazz education at the college level, and his students included everyone from Gary Burton to Roy Hargrove.

A memorial service for Pomeroy will be held this Sunday at Emmanuel Church, where he’ll be remembered as — among other things — teacher, bandleader, and player. Pomeroy was a paradox: a celebrated big-band leader, but also an uncommonly inventive trumpeter whose favorite playing situations were small groups — quintets, trios, duos — in small clubs and restaurants. The trumpeter and big-band composer Greg Hopkins recalls that, “especially later in life, he’d say, ‘Greg, my favorite group is a duo. Anything else is superfluous.’ I said, ‘Herb, don’t say that! You’re negating the first 50 years of your life!’ ”

But there was a common thread: in both modes, Pomeroy was seeking an intimate connection through jazz. And the way he taught young musicians how to play in and write for large ensembles offers a key to his personality. Fred Harris, who now leads the Festival Jazz Ensemble at MIT, met Pomeroy when Harris was in his 20s. He says, “Some people are really nice guys in front of a band, but they don’t produce anything. But Herb was one of these guys who didn’t have to rule by terror. He was one of those rare people who you delivered for because he brought so much of himself and his integrity to it that you just didn’t want to let him down — whether you were a high-school kid or Greg Hopkins.”

Hopkins: “Herb was a master of rehearsing a band because he made you feel important in your part even if your part was not the main focus.” As a player, “He was always part of the fabric of the compositions, part of what was going on at the moment.” He brought that same holistic approach to big-band rehearsals. “He’d want you to understand what the trombones were doing in this one section, or why the saxophones are doing this, or what you should be listening for. He brought everyone’s ears out in front of the band.” His classes were as much about “musical philosophy” as anything. “Tangential subjects: orchestration, personality, shading, dynamics, color, density, texture.”

Pomeroy’s widow, Dodie Gibbons, recalls, “He had such great ears that when he would have a rehearsal and something was amiss, he’d know instantly who or where it was. But rather than calling that person out, he’d say, ‘Okay, saxes, everybody play the third bar. Trombones . . . ,” leading each section in turn through the trouble spot, so that the offending player could hear — and correct himself.

As a jazz musician whose career went back to the ’50s, Pomeroy — who gave up the road for the security of a teaching position — was a contract player, someone who could do it all, whether it was playing with Duke Ellington or in a theater-district pit band. Trumpeter Everett Longstreth, who played in many of those situations with Pomeroy, as well as with the Pomeroy big band, recalls grueling 11-day stretches with the Ice Capades. “We did two three-hour shows a day, three shows on Saturday, of really hard playing. When you were finished with that job, you knew you’d worked.” Longstreth recalls Pomeroy’s dedication to his big band, the mad jumble of talented, discordant personalities that had to be brought together into a cohesive whole. When he led the band at the legendary club the Stable, it wasn’t unusual for the non-drinking, non-smoking, non-drugging Pomeroy to bring a “tired” player to the nearby Hayes-Bickford for a plate of macaroni and cheese in hopes of sobering him up for the third set.