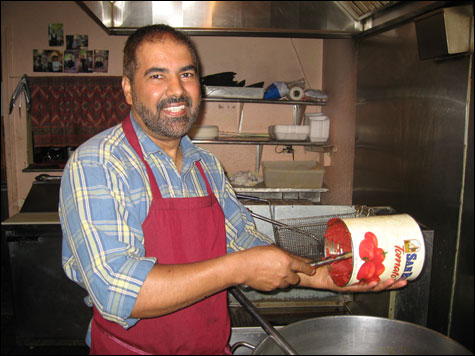

SLINGING SAUCE: Bhupinder Singh at Tandoor.

|

|

Tandoor | 88 Exchange St, Portland | 207.775.4259

|

For those who have tried to cook Indian food at home and found it nothing like good Indian-restaurant food, walk with me past the window painting of a man riding an elephant; through Tandoor’s yellow, purple, and green painted dining room; under Indian tapestries replacing certain foam ceiling tiles. You’ll see a white folding door in the back. Walk through it. Now we’re in Tandoor’s kitchen.

Bhupinder Singh is moving fast. It’s 11:30 am. He’s sweating. He’s not wearing a white chef coat and checkered chef pants, but a plaid flannel shirt and slacks. He’s speaking very quickly to his assistant, who is one of three Indians Bhupinder has sponsored, leading to their citizenship and immediate employment at his restaurant. Bhupinder looks at me, speaking English, much more slowly and deliberately. “I do masala,” he says. “And rice.” Masala is one of two sauces that are ubiquitous in Indian cuisine. The other sauce, to my surprise, is called "gravy," but has absolutely nothing to do with turkey drippings.

In the bottom of a three-foot-tall aluminum pot, vegetable oil is already glistening. Bhupinder tosses in a full handful of whole cumin seeds and three bay leaves. Before I notice he has even left my side, he appears with a small oval plate holding a mass of about a cup and a half of chopped garlic, which he shakes in one motion into the sizzling oil. Then he’s gone and back with another plate. “That’s some fresh ginger. Tasty, no?” He does what looks like swing dancing with a miniature aluminum canoe paddle, swishing the mass of chopped “fresh ginger garlic,” sending a bright tangy aroma thundering into the room.

I scramble after him to the spice bins. With a large serving spoon, he scoops colorful mounds of powders onto a plate: three spoonfuls of white salt, two spoonfuls of grayish brown coriander, two spoonfuls of yellow-brown cumin, a half-spoonful of light green fenugreek leaves, a half-spoonful of outright orange turmeric, and (as if this weren’t already a mystical concoction) finally a half-spoonful of garam masala, a mixture of coarsely ground green and black cardamom pods and whole cloves. This mountain of what I think of as the magical powders of India shoots into the pot, and Bhupinder does his dance again with the paddle. The fresh roots and dried spices are snapping and sizzling, melding their independently off-putting powers into something that, in about four hours, is going to go down like love, scintillating, yet smooth.

He adds a gallon of water, and two #10 cans of tomato paste, and then pulls out a whisk as long as a yardstick. He stirs and suddenly I see it: the sauce, still unfinished, but detectable, the reddish-brown beginning of no fewer than 10 main courses on the menu, including any item with the word "masala" in it, and some without, like Malai Kofta, Shahi Paneer, and Shahajahani Murgh. Bhupinder adds more water so the pot is two-thirds full. He tells me it needs to cook for two and a half hours, followed by another hour with light cream mixed in.

And that’s just the sauce! The marinating and cooking of the shrimp, fish, lamb, or chicken is yet another story. As is the rice. I find my conclusions. Reasons why the Indian food you cook is nowhere near this good: you don’t have fenugreek; you don’t have the paddle; you don’t have three Indian restaurants under your belt, or a childhood in Punjab province. And you don’t have all day to cook dinner. Luckily, Tandoor is at your service seven days a week.

Email the author

Lindsay Sterling:

lindsay@lindsaysterling.com