|

Now that the jungle is withdrawing, and the wilderness is tenanted, and every inch of Earth’s surface is invisibly cross-hatched by centuries of cartography, the brief of the travel writer has altered somewhat. In the old days — in the 13th century, for example, when the great adventurer/bullshitter Marco Polo was in his prime — it was enough for a man to sail away for a year or two, come back, and then simply report on what he had seen. Or not seen, in Polo’s case. “Andaman is a very big island. . . . You may take it for a fact that the men of this island have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes like dogs; for I assure you that the whole aspect of their faces is that of big mastiffs.” Polo was doing time in an Italian prison when he dictated Travels, which may account for its pervasive fantastic quality. Somewhere deep down he was an honest man: every one of his whoppers is preceded by a giveaway protestation of veracity, a “You must know” or an “I tell you in all truthfulness.” (One may imagine the diligent Rustichello da Pisa, Polo’s jailhouse amanuensis, rolling his eyes as he took down the details.)Penguin’s “Great Journeys” series, published this month, excerpts the great texts of travel literature, from Herodotus to Ernest Shackleton, in 10 slender and beautifully designed paperback volumes. (The passages from Polo’s Travels are collected under the title The Customs of the Kingdoms of India.) The closest to us degenerate moderns in terms of sensibility is undoubtedly Mark Twain, an extract of whose The Innocents Abroad, originally published in 1869, appears as Can-cans, Cats &Cities of Ash. Twain cruises the Mediterranean with some fellow Americans, making noisome and heretical pit stops in the Azores, Morocco (“The Emperor . . . is a soulless despot.”), Italy, and Greece, but it is the well-groomed nation of France that really rouses his native anarchy:

Occasionally, merely for the pleasure of being cruel, we put unoffending Frenchmen on the rack with questions framed in the incomprehensible jargon of their native language, and while they writhed, we impaled them, we peppered them, we scarified them, with their own vile verbs and participles.

As a comedian Twain was pitch-perfect:

We went to see the Cathedral of Notre Dame. — We had heard of it before. It surprises me, sometimes, to think how much we do know, and how intelligent we are. We recognized the brown old Gothic pile in a moment: it was like the pictures.

The current satirists of cretin America, of whom George Saunders is the chief, were but twinkles in Twain’s eye. The only thing that dates Can-cans, Cats & Cities of Ash as literature is its extraordinary latitude of style, as the author swings irrepressibly from sarcasm to rhapsody:

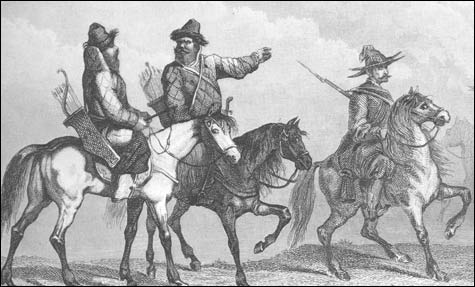

In cool mornings, before the sun was fairly up, it was worth a lifetime of city toiling and moiling, to perch in the foretop with the driver and see the six mustangs scamper under the sharp snapping of a whip that never touched them; to scan the blue distances of a world that knew no lords but us. . . .

Twain’s sister in exaltation in the “Great Journeys” series is the formidable Isabella Bird, whose 1879 Adventures in the Rocky Mountains is a prolonged gasp of pleasure at the American landscape. (Incidentally, one suspects that Bird also supplied the prototype for the character of Mattie Ross, heroine of Charles Portis’s 1968 masterpiece True Grit: Isabella and Mattie share a dislike of “pistol affrays” and a pronounced impatience with men of less than average intelligence.)

As an antidote to both the profane buoyancy of Twain and the purpleness of Bird, a swift dose of Ernest Shackleton’s Escape from the Antarctic is indicated. This great Brit, stranded with his crew on barren Elephant Island after their ship the Endurance is crushed by ice, decides to make a run for it and get help: with circling ice herds menacing their exit, Shackleton and a scratch crew of five board a tiny boat and push off into freezing seas. Eight hundred miles later, ragged, frostbitten, and starved, they stagger down a mountain into the whaling station at Stromness, in the Falkland Islands. The Endurance set sail from Plymouth, England, in 1914. It is now 1916. “Tell me,” Shackleton enquires of the whaling station manager, “when was the war over?” “The war is not over,” the manager tells him. “Millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad.” The irony here is mythic, below-zero, like something out of Nietzsche or Kafka: at the bottom of this extraordinary effort to rejoin the world lies a revelation of the world’s barbarity.