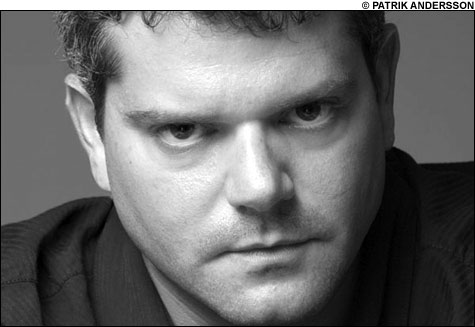

SWEET SINNER: Auslander writes about his first traif experience as one might a first-sex scene.

|

|

Foreskin’s Lament

| By Shalom Auslander | Riverhead | 320 pages | $24.95

|

Shalom Auslander’s memoir, Foreskin’s Lament, begins with a hoot of a first chapter, one that’s sure to be quoted on nationwide Jewish e-mail chains. In it, Auslander considers the twisted relationship he and other Jews have with their God. God, he points out, is a big prick: striking Moses dead just before he reached the Promised Land, making Sarah barren because she giggled. And compared with other moments in history, these were good moods. “Some days he hated us so much, he killed us; other days, he let other people kill us,” writes Auslander. Yet despite all that, “This was the song we sang about him in kindergarten: God is here, God is there, God is truly everywhere!”

Auslander’s own twisted relationship with God comes from a childhood spent in an Orthodox community in Monsey, New York. His father, a humorless drunk, isn’t the best Jew in the world, but he does command that his sons be good ones. His mother, a dour sort, has a habit of rushing to bury the dairy and meat utensils in the house plant should they touch. Along with his Yeshiva teachers, his parents threaten him often with the promise of God’s wrath.

Of course, the tighter the reins, the more likely — and stranger, as it happens — the rebellion. Told that in Heaven he “would be boiled alive in giant vats filled with all the semen I had wasted during my life,” he lustily constructs a makeshift woman from his mother’s laundry. Told that eating traif (non-kosher) food is a loathsome sin, he becomes addicted to the stuff.

Auslander writes about his first traif experience as one might a first-sex scene. It’s full of excruciating descriptive detail, the indifference of the world at large juxtaposed with a tense interior narration as he works up the nerve to buy a Slim Jim:

“This is what Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said that God said about someone who eats non-kosher: God loathes him in this world and He tortures him in the next.

I don’t have all day, kid, said the Snack Shack man. — Anything else?”

Later, he discovers that he’s short 75 cents.

“This was God; this was God Himself, intervening in my behalf, giving me one last chance to pull me back from the brink of . . .

Skip the soda, I said.”

Auslander revisits these scenes of his Orthodox upbringing in Monsey from his adult vantage as a relatively secular Jew living in Woodstock. In these passages, the author, who is “mostly estranged” from his parents, can’t shake himself free of the God that was thrust on him as a child. He’s plagued by the old demons, as well a new one: he must decide whether to circumcise his infant son — should his pregnant wife, Orli, give birth to a boy.

Auslander turns his fear of God into a running joke: with each misfortune, he looks skyward. Sometimes he’s funny, as when, with Orli, he walks 14 miles to Madison Square Garden (to avoid driving or taking public transportation on the Sabbath), only to see the Rangers lose and then enquire, “Tell me, God, . . . what nonsensical, inscrutable law did I break that warranted this?” But by the time he starts chalking up everything to the wrath of the Almighty — from a bad experience in bed to his relationship with a fat girlfriend — the joke has become tiresome.

A typical low point comes when he spies the breasts of two scantily clad women on their way toward the Woodstock coffee shop in which he is working on his book. These breasts, Auslander asserts, are God distracting him from the task at hand: “this is Him, not taking any chances, covering the bases of my myriad perversions.” If only God had taught Auslander that some thoughts are better left unexpressed.

SHALOM AUSLANDER | Brookline Booksmith, 279 Harvard St, Brookline | October 11 at 7 pm | 617.566.6660