A MOVING STILLNESS: Of Mice and Men.

|

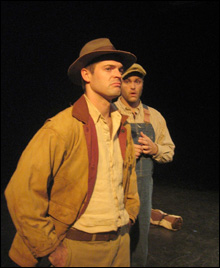

“Tell how it’s gonna be,” Lennie prods George, again and again. He’s heard it a million times — how there’ll be a house, vegetables, chickens, good company, and the fluffiest of rabbits — but he never tires of the story. So again and again, George retells their gleaming future, softer, sure, perfectible. As they and other hard-living folks seek out something better, they reveal the excruciating yearnings and fears involved in sharing a little softness. Mad Horse opens their season with a rich, devastating production of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, under the fine direction of Christine Louise Marshall.

George (Craig Bowden) and Lennie (Burke Brimmer) are Steinbeck’s timeless buddies of American bathos: The shrewd working-stiff drifter, and his ward, the gentle, soft-headed giant who doesn’t know his own strength. In the slim times of 1937, the two find work baling at a ranch in Salinas, California, where their dream is standard-issue American: a stake to sow in acres all their own. They’re working for a mean, bottom-line boss (Mike Kimball) and his short, jealous bully of a son, Curley (J. Paul Guimont); and living with a bunkhouse of laborers whose toil gets them about as far ahead as the cathouse and back. George and Lennie are a pair among loners, as George keeps the mentally compromised Lennie out of trouble.

|

Of Mice and Men

| by John Steinbeck | Directed by Christine Louise Marshall | Produced by Mad Horse Theatre Company | at the Portland Performing Arts Center’s Studio Theater, through October 14 | at Maine State Ballet Theater in Falmouth, November 1-11 | 207.730.2389

|

It’s pretty strange around here, as the perceptive Slim (the excellent, understated Dave Currier) keeps repeating, to see a couple of guys taking care of each other. For the most part, everybody in these parts shares two qualities — a desperate longing for communion and security, and the visceral fear of one another than comes of never finding it. They illustrate myriad variations on human isolation: Curley is poisoned by thoughts that his wife (Ariel Francoeur) isn’t truly his; she seeks companionship and is harshly rejected to avoid trouble. Crooks (Lowell Jeffers), a hunch-backed black man, sleeps away from the others; and elderly, lame-handed Candy (Chris Horton, whose work here is piercing) fears his future in a country that’s not kind to old men, once they’ve passed out of usefulness.

Marshall’s strong cast makes the walls between these people painfully tangible in tone and gesture — Curley’s vicious, terrified bark; Crooks’s defensive bitterness; Slim’s sharp and wary gaze; Candy’s slouching sadness. We see these men after work, when they’re usually too beat and broke to do anything but hang around, and in Marshall’s blocking, their stillness is poignant for much of the play. But she also weaves a layer of movement underneath — Slim’s hands braiding rope, George flipping Solitaire, the constant rocking of Lennie’s hands. These rhythms suggest a human persistence beneath the stasis, and also serve as a fine counterpoint to the moments when the action suddenly flares.

And flare it does, with often genuinely frightening stealth. Despite a few rough spots (the wrenching scene in which Candy is brow-beaten into letting his old dog be shot could use some tauter pacing, though the moments between his consent and the off-stage shot are riveting), Marshall’s direction is intimidating. On opening night, a sudden surge of violence between Curley and Lennie was intense enough to draw actual cries from the audience.

Even more fraught are the scenes in which characters approach wary communion, because for all our joy in it, we know better than to hope for its hold. The slow-growing warmth between George and Slim, between Candy and George, between — most painfully — Curley’s lonely wife and Lennie is so radiant that you want to look away.

The play’s final, nearly unbearable moments bring an exquisite rawness to Bowden’s George, a wounded human chaos of love, rage, and grief. What redemption we can find lies here, somehow. It’s in his agonizing, candid compassion for this human bond — so often withheld by so many others — that there can be hope for something better than what has passed.

Email the author

Megan Grumbling: mgrumbling@hotmail.com